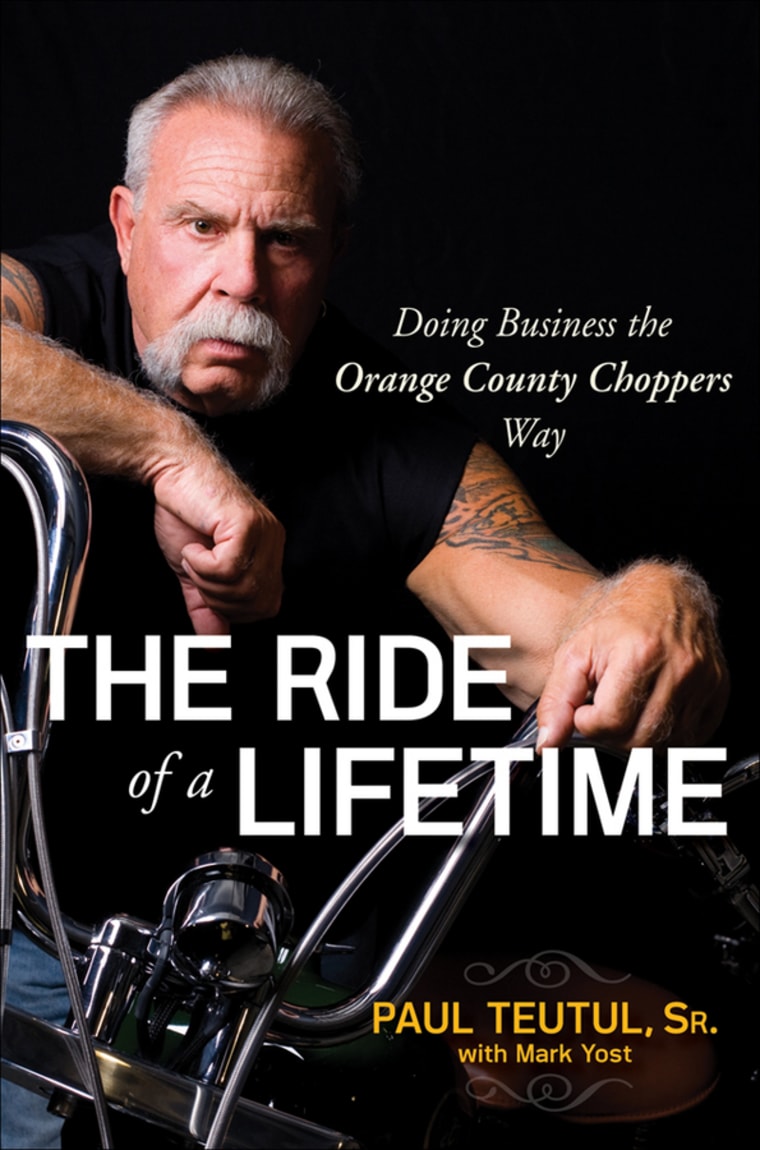

The star of the hit TLC show “American Chopper” and founder of his own family business, Paul Teutul Sr. shares advice about running a business in his book, “The Ride of a Lifetime.” Teutul founded Orange County Choppers in 1999, and grew his hobby into a 70-plus-person operation that produces and sells 150 custom bikes a year. In this excerpt, he writes about battling alcoholism and finding the clarity of mind to develop his company.

Sobering up

I remember the day exactly. It was January 7, 1985 — 11 years after going into business together. Twenty years of hard drinking and partying since the age of 15 had finally caught up with me. My body was literally falling apart. I was coughing up blood. Over the years, I had wrecked a dozen or more cars. On the weekends, I would wake up and not know where I was or how I'd gotten there.

So on January 7, 1985, I decided that I'd either have to sober up, or die. I chose to die. I told my wife, Paula, who had been through so much with me and should be nominated for sainthood, that as much as I would like to get sober, I couldn't. So my only choice was to die.

Somehow, she talked me into going into rehab, something I thought I'd never do. But I wanted to have one last good drunk. So the day before I was set to go into rehab, I got totally plastered. I drank a half-gallon of wine, a pint of brandy, and I took six Valiums. I woke up the next morning completely hung over. I had promised my wife that I would go, but I just couldn't. And you want to know why I couldn't do it? Because I couldn't leave my business. I thought that if I went into rehab that I'd lose everything I'd accomplished up to that point: my business, my customers, my reputation. In my mind, if I went away for 30 days, I thought it would all go away and I'd have to start all over again.

You also have to remember that throughout all my years of drinking and doing drugs, I went to work no matter what: broken arms, smashed fingers, the flu. Even toward the end, when I was spitting up blood, I showed up to work every day. No matter what. So in my mind, I couldn't take 30 days off from work, even if it was the only way to save my life. I couldn't lose everything that I had gained over the past 11 years. There was an uncertainty there that I simply couldn't handle.

But I'm a man of my word. And my word is my ironclad bond, and my vow to my wife had been to get sober, and that was what I was going to do. So instead of checking myself into rehab, I went to an Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meeting — something I'd said I would never do. For the next nine years, I never missed a meeting. Thankfully, in January 2009, I had been sober for 24 years.

That was the beginning of a whole new life for me. A life that — I finally realized — was full of choices. And one of those choices was not to drink, although it took me a while to figure that out. Once I went to that first AA meeting on January 7, 1985, I never took another drink. But I was tempted every day. That's because I was surrounded by drinkers. My partner, John Grosso, and all the guys who worked for us were all boozers. I was the only guy who had decided to sober up, so there was constant pressure on me to drink. I would be on the job site with these guys, or in the truck, trying not to drink, and they'd be passing a bottle of whiskey or downing a case of beer. It was a challenge every day.

For a while, I thought I could deal with it. I thought I could be around them and not drink. They'd send me out for a case of beer and a bottle of Black Velvet at 2 P.M. And, like a dummy, I'd go get it for them. I didn't think that just because I had stopped drinking that I couldn't hang out with my drinking buddies.

About a year into AA, I was not drinking, but it was still a daily struggle. It was one of the hardest things I'd ever done not to grab hold of that bottle that was being passed around the truck and take a swig. I didn't know how long I could keep saying “no.”

Then a guy in AA told me something that saved my life. He said, “If you don't drink just for today, you may be dead tomorrow. So just worry about getting through today.” That was it for me. I finally got it. I understood that I couldn't worry about being sober a month or a year or five years from now. It was a day-to-day struggle. And if you simply don't drink for today, then you're winning the battle. It sounds so simple — “Just don't drink for today” — but it saved my life.

A new life When I stopped drinking, it opened up a whole new life for me — a life full of choices — and, for the first time ever, I was in charge. It was also the end of the life I had been living. The life of drinking and drugs that had ruled my life and held me back professionally. And that meant the end of another partnership.

That's because John Grosso had not only been my business partner, but he had also been my drinking buddy. After we'd bang out a job, we'd spend the afternoon on a bar stool somewhere, talking about all the great things we were going to do with the business. Of course, we never did them. That's because it took all of our energy to just get out of bed in the morning, get to the job site, and then get to the bar. It was a vicious cycle.

When I got sober in 1985, John tried to get sober, too. Unfortunately, he didn't make it. One year after getting sober, I finally told all the guys that there was no more drinking in the shop, no more drinking in the truck, and no more drinking on the job site. They had to stop. It was my choice, and I embraced the fact that for the first time in my life I had control over making that decision. Needless to say, most of my employees who were my old drinking buddies disappeared. They weren't going to tolerate that. Old Paulie simply wasn't as fun as he used to be. Maybe not, but I was a hell of a lot more focused. And it started to show.

Two years after getting sober, I built my own shop. John Grosso still worked for me, but he was no longer my partner. He was just an employee. I tried to reach out to him. I would say, “Listen, John, if I can do it, anybody can do it.” I thought I could get through to him. I drank with this guy for 10 years. In fact, I drank harder than he did. He would go to a couple of AA meetings, get sober for a week, and then start drinking again. It finally got to a point where he was still coming to work drunk. Eventually, I had to say, “You can't come here, you can't be drinking, and you can't be drunk.” I told him, “Either get sober or you have to leave.”

He chose to leave. It was one of the hardest things I ever had to do, but it was a sign of my own personal growth in my sobriety. John moved to Florida and went to work for my brother-in-law again, but he came back to Orange County about six months later. He was dying. His liver was gone. A few months later, he died. He was just 35. That's an interesting number: 35. Only one in 35 people end up staying sober. I guess I was one of the lucky ones — and still am.

I was sober, I was thinking straight, focused and driven, but I still shunned partnerships. That's because I realized that when I was drinking, the alcohol and the drugs blurred my vision. But being with a partner who doesn't share your vision can do the same thing. That's why I don't do partnerships. Not then, not now.

But as my business took off like never before, I realized that I couldn't do everything on my own. Two years after getting sober, I bought a piece of property on Stone Castle Road in Rock Tavern, New York, and built a new shop. I also started diversifying. The residential work was slowing down, so I moved into commercial work. I became a fabricator, started to develop relationships with contractors, and accumulated quite a bit of work. Again, it's about realizing that I had choices. I wasn't locked into just one type of business.

Because I was now thinking clearly, I had the good sense to make the building about twice as big as it needed to be at the time. I say “at the time” because in the span of just a few years, I ended up tripling the size of the facility and renting another building down the street. As my business grew and diversified, I went from just four employees to more than 70. And it's all because I was sober, thinking clearly, and driven. More importantly, I was able to take that drive that was always there and apply it in a positive way. Before, my drive was put into just showing up for work. “What can be wrong with me?” I used to think. “I get up and go to work every day.” But a lot of energy was being wasted.

Now, I don't want you to finish this chapter by thinking that all of my experiences with partnerships have been bad. That's simply not true. My issue is exclusively with having a partner inside the business. I don't want someone who, as a partner, has the same input as me into the direction and growth of the company. I'm totally against those kinds of partnerships, for all the reasons I've listed so far.

What I am not against are partnerships outside the business, because that would be simply impossible. As focused and driven as I was after I sobered up, I quickly learned that I had to make limited partnerships with people who could help me achieve my dreams and my goals. A clear example of that was a partnership I started back in the early 1970s, when I first started building custom bikes in my basement.

Ted Doering had a company in Newburgh, New York, called V-Twin Manufacturing. Back then, he was selling custom and vintage motorcycle parts out of his barn. When I needed a part, I would walk into his place — he'd have a piece of straw in his mouth, the floor was nothing but packed dirt — and we'd bargain for parts. Today, he's one of the largest distributors of aftermarket motorcycle parts in the world.

Initially, Ted didn't like the fact that I was going to take his parts — like a gas tank — and cut them up to make them look the way I wanted. But we eventually became friends. More than that, he was an early mentor. Ted was the guy I would reach out to when I would build bikes in my basement for myself, long before I started Orange County Choppers. He was the guy who would point me in the right direction in terms of the parts I needed to build the bike I wanted to create. And because he carried a lot of vintage parts I needed to customize the old-style bikes I liked back then, he was a great partner. I could go into his place and build a whole '57 chopper out of parts. In short, Ted Doering was my first successful business partner.

In the 1970s, I wanted to build a panhead chopper with a Patogh frame, an old-school bike for myself. We'd start at the rear tire and work our way all the way up to the front end. He walked me through the whole thing. That's how I started building the early old-style bikes. Eventually, I didn't need Ted anymore. I had built so many bikes that I could figure it out myself. But he was a good partner and supplied me with most of what I needed in the early days.

From these humble beginnings, I built Orange County Choppers. While it's a hugely successful business, it wouldn't exist without the passion I have for motorcycles. And after having just read the previous chapter, you'll be surprised where I got my passion for customizing old motorcycles.

Excerpted with permission from the publisher, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., from "The Ride of a Lifetime," by Paul Teutul, Sr. © 2009 by Paul Teutul, Sr.