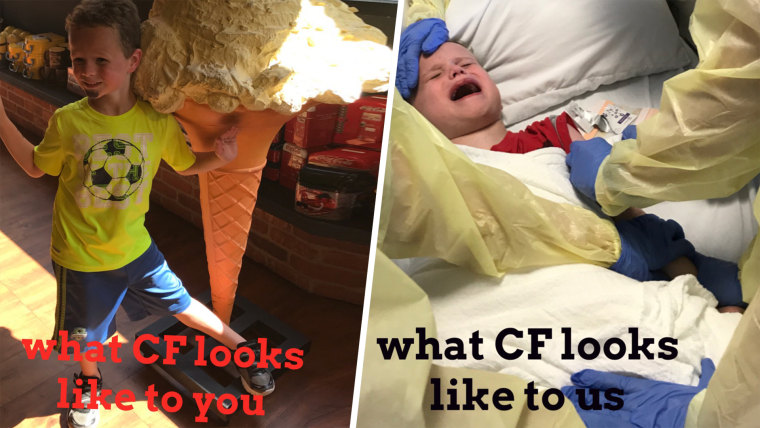

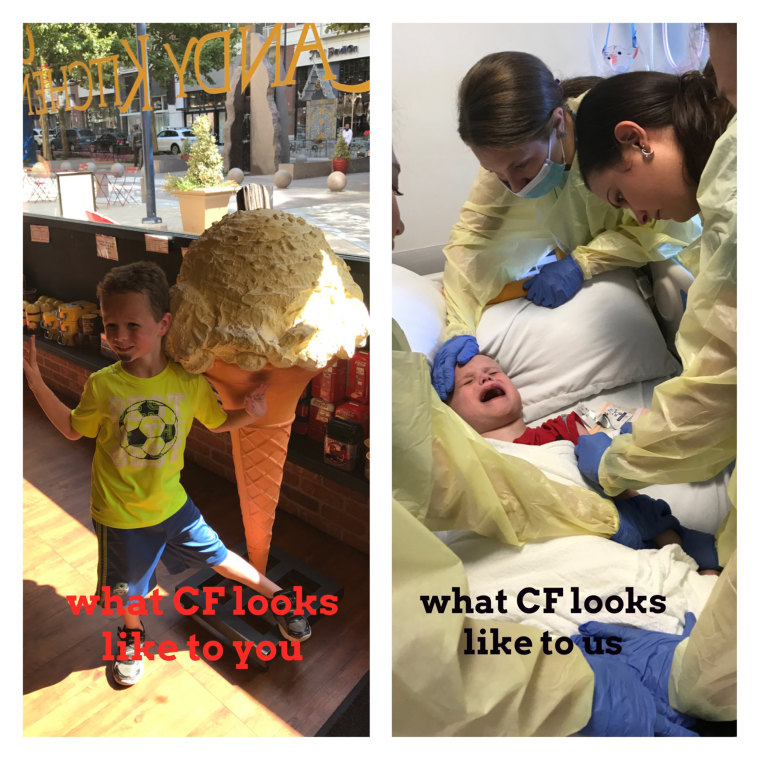

When Tasha Nelson’s son Jack was only a month old, she discovered he had cystic fibrosis (CF). Very quickly, as the mother of a child with a serious illness, she learned that she'd have to be an advocate for his care.

But now she and other parents like her are tackling a new role — political advocate. A Republican-sponsored tax bill in the U.S. House proposes getting rid of the "orphan drug" tax credit, which provides incentives to companies researching, developing, and producing pharmaceuticals for conditions that affect 200,000 or fewer people.

“Any dime you take away from a company that is working toward saving my son’s life is an insult to my family,” said Nelson, of Manassas, Virginia.

Parents of children with fatal or life-limiting illnesses are used to fighting with insurance companies and bureaucrats to make sure their children get proper treatment.

“We spend the largest percentage of our day to get Jack what he needs in order for him to fight cystic fibrosis,” she told TODAY.

Nelson has organized fundraisers for CF research and does social media advocacy. And, she’s considering taking Jack to Capitol Hill with the Little Lobbyists to lobby against the recent tax plan.

Never miss a parenting story with the TODAY Parenting newsletter! Sign up here.

“If the tax break is taken away the drug companies may not have the resources to help us,” Nelson said.

Orphan drugs cost a lot to manufacture without much chance of recouping costs (because of the small number of people affected by the disease). That's why the 1983 Orphan Drug Act gave drug companies tax credits to offset the cost of specialty drug development. If the tax credit is wiped out, the National Organization for Rare Disorders estimates that 33 percent fewer orphan drugs will reach consumers.

“The Orphan Drug Tax Credit is one of the most important incentives for spurring the development of therapies for individuals with rare diseases, and its repeal is wholly unacceptable,” said Peter L. Saltonstall, president and CEO of NORD in a statement.

Orphan drug sales were $36.1 billion last year according to a report by NORD and QuintilesIMS. Lawmakers proposed the repeal as a way to curb pharmaceutical companies' misuse of the incentives to make profits. Prescription drugs prices have been steadily increasing and people fear that the increased costs lead to more profit for drug companies and less treatment for those who need it.

For parents of children with orphan diseases, the proposed elimination of the credit removes hope. They worry that without the credits, companies could scrap future drug research and development.

“It’s really the loss of potential for treatment,” Courtney Waller, of Williams Bay, Wisconsin, told TODAY.

Waller’s 4-year-old daughter Theodora has Timothy syndrome, a condition so rare only about 50 people in the United States have it. Children with it die from cardiac arrest, normally by age 5.

“There’s really no treatment for it,” she said. “We do what they tell us to do. There’s no guarantee that any of it is working.”

Waller has been calling her representative, House Speaker Paul Ryan. She doesn’t think she’ll sway his opinion. But she keeps trying because she’s fighting for Theodora’s future. The toddler, who loves books and coloring, enjoys being outside but sometimes becomes winded or dizzy and her parents have to warn her to slow down. They always hoped a new treatment would become available for Theodora.

Lately, Waller spends about four hours every day making calls, sending emails, or organizing others in Wisconsin to call their representatives.

“Maybe I can’t change Paul Ryan’s mind but maybe I can get my friend to change her representative’s mind,” she said. “Advocacy has become a full-time job and that’s something I didn’t anticipate.”

Orphan drugs save lives

When Jack was born six years ago, the average life expectancy for people with CF was 28. Today, it is 41.

“It is because of the development of new drugs,” Nelson said. “An example is the drug Pulmozyme. That’s the reason there was a huge increase in life expectancy.”

Pulmozyme helps people with CF breathe better. CF is a genetic disease that causes mucous in the body to thicken and it affects about 30,000 people in the United States.

Jack takes 14 drugs a day and does six hours of breathing therapy to manage it. Despite that, Jack enjoys playing with friends, and he ultimately wants to be a “scientist that cures germs." Orphan drugs could make his dream come true.

One of the arguments for continuing the tax incentives involves company-sponsored copays. While Pulmozyme costs $6,000 a month, the drug company offers it at a deeply discounted price through a copay program.

“No middle-class family can afford a $6,000 medication. It is $200 a day,” Nelson said.

Nelson pays $25 a month for Jack. She feels like the drug helps him tremendously but still hopes for a cure.

Rebecca Mauldin's 1-year-old son Jonathan' life was saved by an orphan drug.

Jonathan' has spent most of his life battling a rare cancer called Langerhans cell histiocytosis after being diagnosed at 3 months old.

“He had extensive, painful lesions and tumors on his skin and his bones. It was also in his liver and spleen,” Mauldin, of Edmond, Oklahoma, told TODAY via email.

While an existing chemotherapy is the common treatment for Langerhans, Jonathan’s cancer was so aggressive that his tumors continued growing after it. Doctors switched him to an orphan drug developed to treat childhood leukemia.

“Ten years ago, his chance of survival would have been only 18 percent.”

Thanks to a drug company’s copay program, Mauldin only pays $10 of the $1,500 monthly cost of a targeted therapy drug for melanoma that is currently part of Jonathan's ongoing treatment. She wonders what life would be like without the copays and new drugs. That’s why she’s calling her representative and asking friends and family to do the same.

“If these drugs weren’t available, I likely wouldn’t have my son here today, running around the house with the biggest grin and most contagious laugh. This drug has been a miracle,” she said.