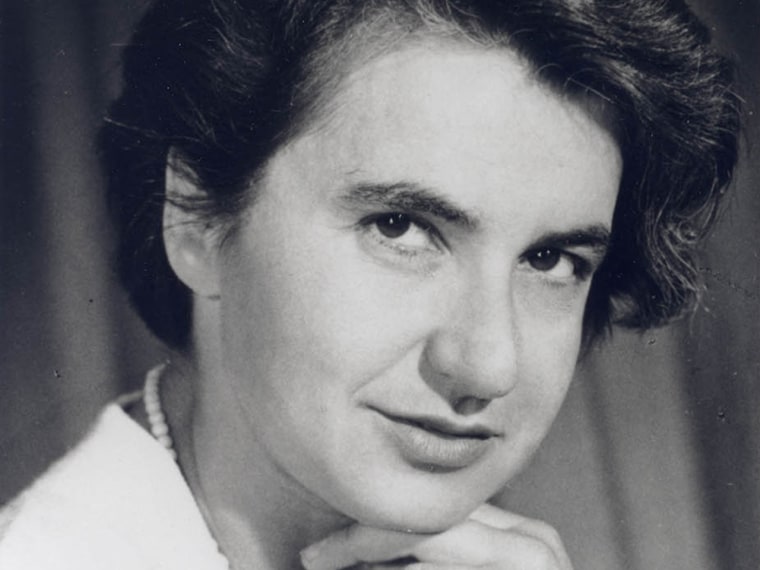

A photographer of very tiny things, Rosalind Elsie Franklin was a skilled chemist, one of a team that first understood, in the early months of 1953, that our DNA is elegantly and economically arranged in twisted double helices.

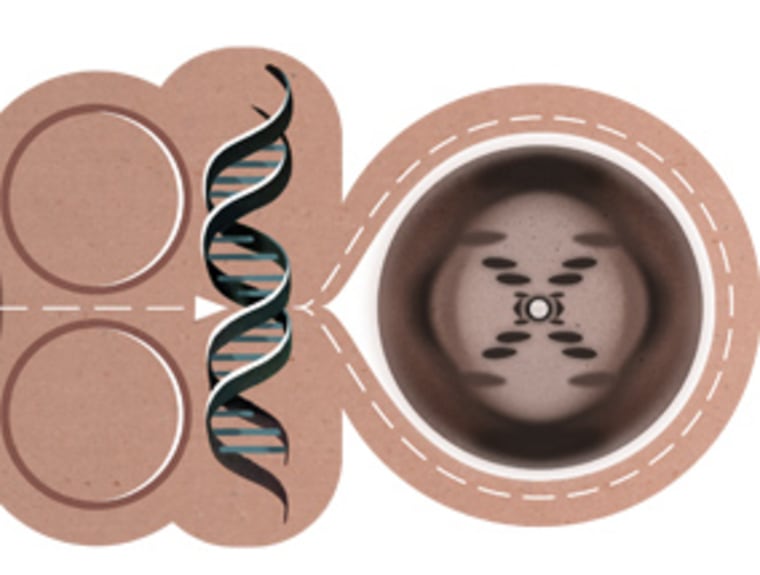

Today, in a Google Doodle that includes a reference to one of her DNA photographs, Google reminds us of a historic moment in science, and of the 93rd birthday of a scientist who contributed to it.

When James Watson and Francis Crick were building ball-and-stick models to piece together the theoretical structure of DNA, independently, at King's College London, Franklin was blasting X-rays through the molecules, taking portrait shots of their structure.

As the story now goes, a glance at one of those photographs helped Watson and Crick run the final last steps to the finish line, publish an iconic paper in Nature, and win the Nobel Prize for Medicine for their work as discoverers of the structure of the code of life.

According to Brenda Maddox, who researched Franklin's work for her biography The Dark Lady of DNA, "from the evidence in her notebooks, it is clear that she would have got there by herself before long."

Franklin's name was not included in the Nobel lists, though her colleague who shared her photographs was named along with Watson and Crick. Some say she was left out because of lab relationships, and because she was a woman. Others insist she was passed over because, diagnosed with ovarian cancer at 37, by the time the Nobels came knocking, she was dead.

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about science and technology. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Google+.