About 6,100 years ago, an unnamed Stone Age chef made culinary history when she flavored a simple dish of deer meat or fish, cooking in clay pot over an open wood fire, with the pungent ground seeds of the garlic mustard plant.

Perhaps it was inventive genius at work, perhaps it was a stroke of luck — those details have been lost over time. But the recipe — the earliest evidence of humans flavoring their cooking with spice — has survived.

Researchers at the University of York analyzed burnt food remains from clay cooking pots found in Neolithic dwellings in Denmark and Germany. On the clay, along with meat fats or traces of fish, they found the distinct remains of garlic mustard seeds.

"What we found is that it's definitely being cooked with, mixed with the food," Hayley Saul, a lecturer in York's department of archeology, told NBC News. While cumin, coriander, capers, basil, poppy and dill have been collected at other sites in southern Europe, the Middle East and India, some older, they may have been around for medicinal or even decorative purposes. This is the earliest conclusive evidence of a spice's use in ancient cuisine.

And it still tastes good. Not the 6,100-year-old pot crust, of course, but the basic garlic mustard seed recipe, which Saul cooked up. "It went down very well," she said. Not surprisingly, to her the spice tasted a lot like the mustard seeds used today.

Crushing the seeds of the plant releases their flavor, Saul found. Also, because no whole seeds were found in their "very well preserved" samples, Saul and her colleagues — who present their findings in the Aug. 21 issue of PLOS ONE — deduced that the Neolithic communities used well-ground seeds rather than whole ones in their cooking.

A majority of the fats found in the pots were fishy preparations. Meat fats were also identified, and are likely to come from roe deer or red deer, which would have been the dominant ruminants in the area at that time, Saul said.

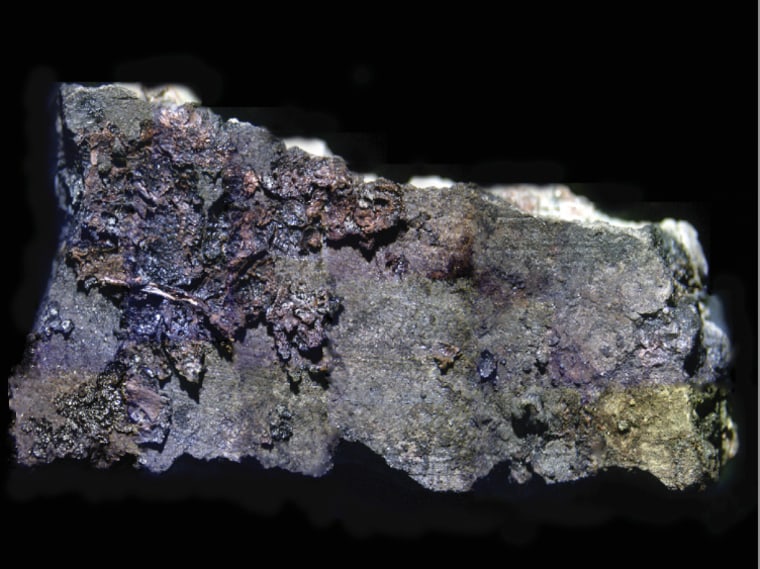

Unlike animal bones, plant matter like leaves and seeds don't typically last too long in archeological samples, unless they're preserved in conditions that are very wet or very dry. To identify the garlic mustard, the researchers looked for phytolith "microfossils" — patterns of silica that plant cells lay down. Though tiny, those tend to stick around, like a cellular skeleton of sorts, and can be detected under an optical microscope.

Plant families and species have multiple signature patterns, and after comparing against a phytolith record of 120 species, Saul and the team identified the trace from the burnt remains as garlic mustard. The seeds were found in eight vessels collected from three sites in Germany and Denmark.

Before humans in northern Europe turned to agriculture a few hundred years later, the turn of the 5th millennium B.C. came with a "a period of a few centuries where people [were] investing in creative culinary experiments," Saul said. Though the spice itself fell out of use in later years, the tradition of spicing foods could have continued, she said.

Earlier this year, Oliver Craig, Saul's co-author, dated the earliest cooked fish stews to Jomonic Japan at the end of the last ice age by examining the burnt residue on 15,000 year-old cooking pots. Using similar biochemical analysis techniques, the first cultured cheeses have been linked to neolithic farming communities 7,500 years ago.

More on ancient food and living:

- Earliest fish stews were cooked in Japan during the last Ice Age

- A votre sante! The first French wine was medicine — and tasted like it

- Jello-O shots from the dawn of time

- Cheers! Eight ancient drinks uncorked by science

In addition to Hayley Saul, the authors of "Phytoliths in Pottery Reveal the Use of Spice in European Prehistoric Cuisine" published in PLOS ONE include Marco Madella, Anders Fischer, Aikaterini Glykou, So ̈nkz Harz and Oliver Craig.

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about science and technology. You can follow her on Facebook, Twitter or Google+.