First there was Albert Einstein: genius, revolutionizer of the physical world, champion of Zionism, hero of pacifism.

Then there was Albert Einstein™. He is another thing entirely.

Albert Einstein™ is a brand name. It belongs to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and is administered by The Roger Richman Agency Inc. of Beverly Hills, Calif. The Roger Richman Agency Inc. is very particular about the brand. “When written in copy on all materials, the name ‘Albert Einstein™’ must always bear a ™ symbol,” it insists.

It is a lucrative trademark. Over the years, Einstein has burrowed himself into the world’s consciousness as the pre-eminent symbol of all things brainy, and marketers like their products to be considered brainy.

For example, Apple Computer and Micrografx Inc. have licensed his likeness to sell computers and software, respectively. Krone sells a $6,950 sterling silver fountain pen named for him. The Walt Disney Co. runs a division in his honor that markets merchandise to educate infants and toddlers — Baby Einstein. All of those uses, of course, were properly licensed.

Somewhere along the way, however, Albert Einstein™ got hijacked by hucksters. These are also among products you can buy today, some of them unlicensed:

- Einstein sterling silver-plated spoons.

- Einstein “Get a Half-Life” coffee mugs.

- Einstein Holy Prayer Cards. They depict Einstein in a purple robe surrounded by a halo, in front of a chalkboard.

- The Ultimate Albert Einstein Carrot Cake. “Albert Einstein’s genius lives on in this carrot cake,” its manufacturer says.

- The “Learn Like Einstein, Earn Like Gates” home business course.

- Einstein wig, mustache and eyebrows sets. “Look like this famous genius!” the company says, although, if you were to wear these muskrat brown attachments, you would look less like a famous genius than you would a famous genius who has had a family of chinchillas die on his head.

- And of course, there’s the Albert Einstein Theory of Relativity Junior Baby Doll. As in lingerie.

“Einstein’s gone beyond the figure that he is into iconic status,” said Jim Tobin, a partner in Brogan & Partners Convergence Marketing, the firm that put K-Mart and Martha Stewart together. “He stands for almost any great idea now.”

The two faces of Einstein

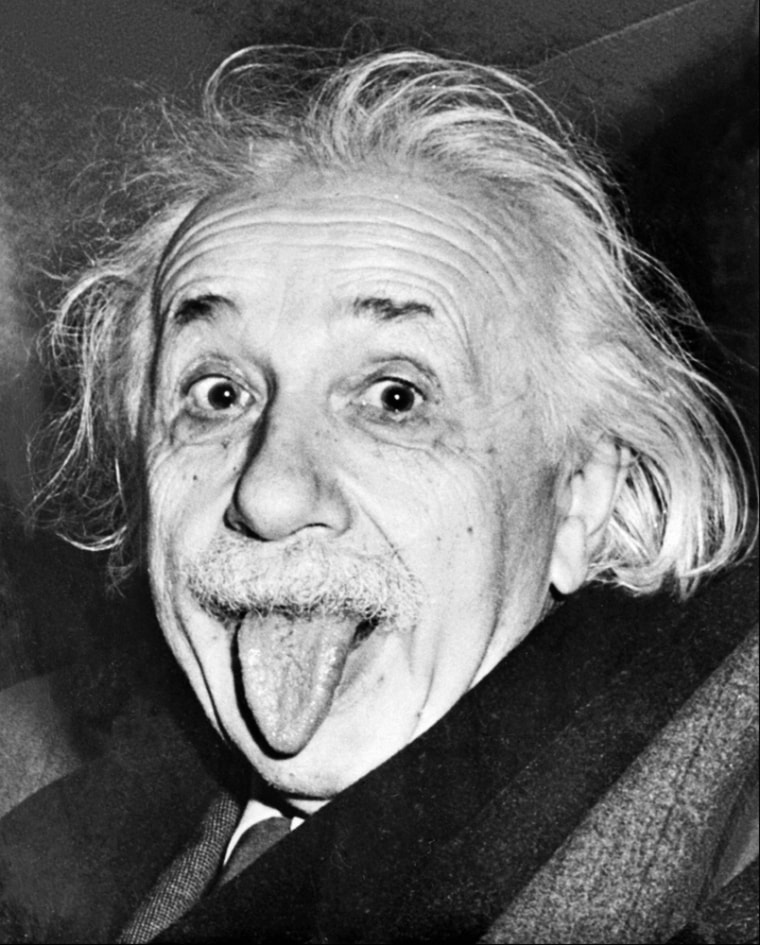

Albert Einstein™, clearly, is a powerful brand. What is interesting is that it rests on a very particular image that we carry around in our heads — that of the old Einstein, with the electrified hair and the droopy mustache and the indifferent wardrobe. The Einstein sticking out his tongue in the famous 1951 United Press photograph. The Einstein portrayed by Walter Matthau in “I.Q.”

This is the Albert Einstein™ who, almost without exception, is portrayed as a nutty professor by the merchandise exploiting his brilliance. We don’t, however, pay much notice to the Albert Einstein of E=mc2. This Einstein — the non-trademarked one who — was a different fellow.

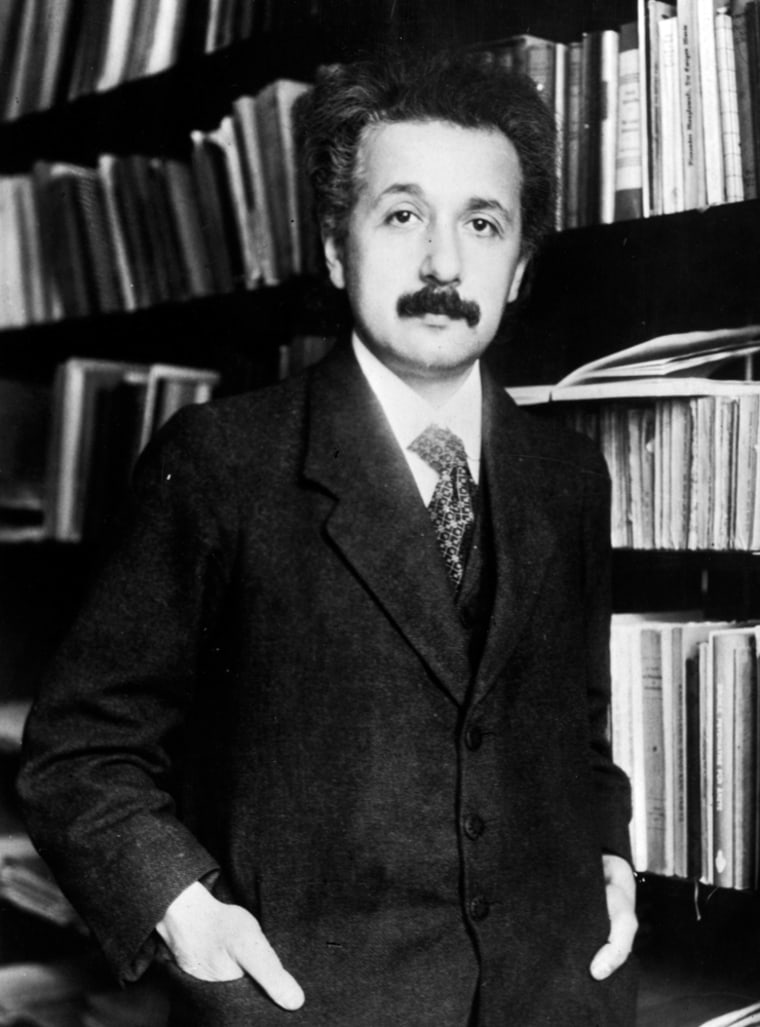

Pictures of Einstein in 1905 show a relatively well-groomed 26-year-old man dressed sharply for the government job he held at the patent office in Bern, Switzerland. This Einstein is vigorous-looking and just a little devilish, with a rather jaunty face. He looks, more than anything else, like a happier Edgar Allen Poe.

Give him a modern makeover, and this Einstein would be right at home before a camera, patiently yet urbanely explaining the intricacies of stem-cell research or the Mars rovers to cable TV audiences.

This Einstein fathered an illegitimate daughter, divorced his first wife and later married his cousin, all the while carrying on more or less open affairs with the “ladies [who] swarmed around him like moonlets circling a planet,” as Time put it in naming him its Person of the 20th Century. (Legend has it that Marilyn Monroe said Einstein was her idea of a sexy man.)

This Einstein is a natural for today’s bloggossip world, a dashing young man about town, easily accessible to the paparazzi as he lives the life of the mind by day and the life of the rake after dark. He is a tabloid dream.

‘Polarizing effect on young scholars’

He is also, perhaps, an opportunity squandered.

When physics organizations decided to mark the centennial of Einstein’s blindingly brilliant work of 1905, they said one of their main goals was to attract students into physics. “The general public’s awareness of physics and its importance in our daily life is decreasing,” says the European Physical Society, the international coordinator of the Einstein Year. “The number of physics students has declined dramatically.”

So physicists latched onto the iconic image of Einstein as a way to get the attention of science students. “You rarely get a chance to have a cultural icon that’s so closely aligned with the message you want to deliver and who has become sort of timeless,” said Tobin, of Brogan & Partners.

Overwhelmingly, however, the icon most of these organizations chose was the old Einstein. Where is the young, cool Einstein?

“The most persistent myth about Einstein is that he was born at the age of 50,” said Michel Janssen, a science and technology historian at the University of Minnesota who edited several volumes of Einstein’s collected papers. He was quoting a favorite saying of John Stachel, the founding editor of the Einstein Papers Project.

The image of the wild-haired professor at Princeton as the talisman of genius is ineffective, said Jeetendr Sehdev, a brand strategist for Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide, the New York-based advertising and public relations conglomerate, who said the “iconic image has a polarizing effect on young scholars considering studying physics.”

“Some students pride themselves on being ‘Young Einsteins,’ but other students are turned off by the images’ unfashionable and stodgy appeal,” Sehdev said.

But Tobin argues that trying to reshape Einstein’s image could muddy his universally recognized brand, which is a proven winner. It runs “the risk of trying to take an icon and pull him out of icon status.”

The old Einstein “is what we now associate with brilliance and what we associate with the breakthrough ideas,” he added. “I think you run the risk of losing the effectiveness of the image in an ad.”

Sehdev, who researches the youth market, acknowledged the universality of the old Einstein and said the image could still be powerful if used the right way. But he would hedge his bets by exploiting ignorance about Einstein as a young man.

He suggested a possible marketing campaign to freshen up the Albert Einstein™ brand:

“‘You think you know what Einstein was about? Well, here’s the reality.’”