If the space elevator dream comes true, robo-cars powered by laser light will roll on a carbon-nanotube ribbon stretching up tens of thousands of miles from Earth's surface, carrying cargo and passengers on a monorail to the sky.

But when Michael Laine, president of the LiftPort Group, manned a booth at a Seattle robotics exhibition last month, he didn't dwell on that dream for the next decade: Instead, he highlighted down-to-Earth applications that could emerge in the next year or two, such as servicing balloon-based platforms for wireless Internet access or aerial surveillance.

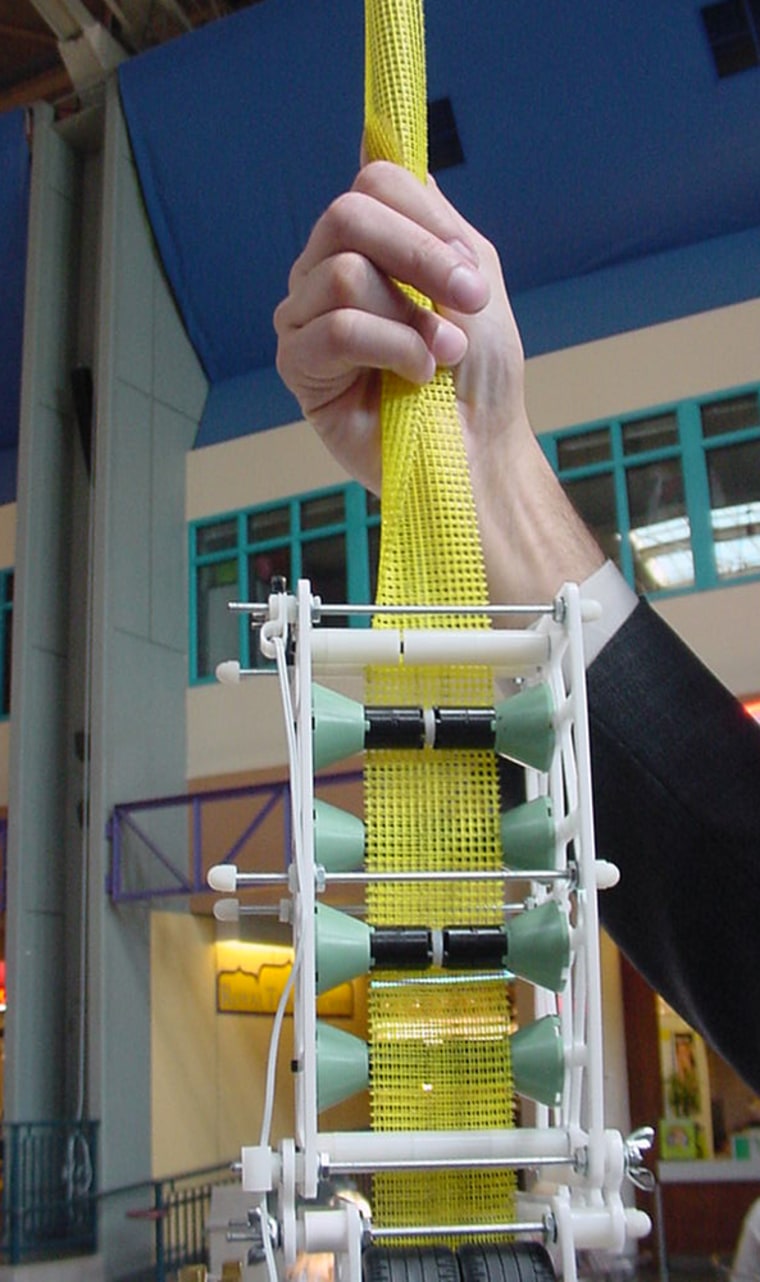

And rather than flashing gee-whiz animations of future spaceships, he flipped a switch on a demonstration robot named "Squeak" that clattered up and down a 10-foot length of plastic webbing.

"Our plan is to do this in an incremental fashion, producing revenue from the beginning," he said.

From science fiction to business model

Bit by bit, the space elevator concept is moving from high-flying science fiction into nitty-gritty business models, and its proponents are turning their focus from the grand scheme to the technologies required to make it work: hardy robotic transports, new super-strong materials and innovative power sources.

Eventually, elevator enthusiasts hope that those technologies will come together to create a space transportation system several orders of magnitude cheaper than current rocket-based technologies. Some of the schemes call for carbon-nanotube ribbons to be unfurled as far as 62,500 miles (100,000 kilometers) into space, connecting Earth's surface to a jumping-off point for exploration or satellite deployment. If the wildest dreams come true, the cost of putting a pound of payload into space could drop from $10,000 to just a few dollars.

In the past couple of years, the concept has gained respectability, thanks to interest from Los Alamos National Laboratory and NASA. Now space elevator evangelists are looking for ways to make the dream pay for itself.

"Private investment is now stepping up with more funding than NASA," Bradley Edwards, an aerospace engineer who has emerged as the prime prophet of the space elevator age, told MSNBC.com in an e-mail. "Once the development is done, it looks like private investment will be much more readily available than the federal funding, and it is likely that the space elevator will go that way."

Toward that end, Edwards recently left his research position at the West Virginia-based Institute for Scientific Research and took the helm of two small companies: X Tech, which is seeking grants for space elevator research; and Carbon Designs, which is focusing on developing high-strength materials.

Pieces of the puzzle

Laine, one of Edwards' former collaborators, is taking a similar approach: His Seattle-area venture is structured to break down the space elevator puzzle into smaller pieces: robotics, carbon-nanotube manufacturing, finance and even media promotion.

For now, Laine's main aim is to get the next generation of researchers interested in those parts of the puzzle. Last week, he conducted a series of seminars at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., and some cadets will be doing projects on technologies related to the space elevator.

"There was some skepticism, which was expected, but it was mostly optimistic," Laine said.

Maj. Tom Joslyn, an astronautical engineering instructor at the academy, said his students were "fascinated" by the concept. "They are young enough to see such a program come to fruition, and many of them see it as a next-generation launch system that could revolutionize access to space," Joslyn said in a LiftPort news release on the academy's role.

LiftPort also has been testing its robots on fabric ribbons attached to tethered balloons, lofted above the Seattle area's hinterlands. "Squeak" is the latest incarnation: a long, narrow contraption equipped with a pint-size electronic brain, batteries, toy-type wheels and guide rollers designed to straighten out a twisted ribbon.

Designed by LiftPort's David Shoemaker, Squeak won the "most innovative robot" award at the Seattle exhibition. Now it's being upgraded for a demonstration planned at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Green Building next month.

"We're going to try to climb up and down 20 stories," Laine said. "Honestly, I think we might fail."

Laine frankly admitted that Squeak isn't sophisticated enough or hardy enough to take on even the first round of commercial tasks he envisions. "A robot that works at sea level is not the robot we need at 5,000 feet or 10,000 feet," he said.

But he said the questions resolved today — wheels vs. treads? batteries vs. solar power? — would yield dividends tomorrow.

Contest plans move forward

That's the kind of work Ben Shelef is trying to encourage with the "Elevator:2010" competition, which is aimed at rewarding innovations in the development of climbing robots like Squeak as well as stronger ribbon materials and light-powered propulsion systems.

"With Elevator:2010, we're not claiming to develop technology," Shelef said. "We're developing public awareness."

Like Laine, Shelef and his colleagues at the Spaceward Foundation are recruiting student teams to compete in the inaugural contests for climbers and ribbons, tentatively scheduled for next June. Taking a page from the playbook for the X Prize rocket competition, Elevator:2010's sponsors would offer annual prizes of up to $50,000.

Shelef is still working on the sponsorship arrangements, but he said the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics already has agreed to help promote the Elevator:2010 competition.

"It gives us credibility," he explained. "We have something, not from space enthusiasts, but from an engineering organization. ... They will get a lot of engineers working on it."

If the technologies behind the space elevator come to be seen as credible, that will make Laine's job that much easier the next time he visits the Air Force Academy. He already knows the concept can capture the imagination of future engineers.

"I told them, 'This is about a sense of adventure,'" Laine said. "The kids' eyes just lit up."