The first truly Earthlike alien planet is likely to be spotted next year, an epic discovery that would cause humanity to reassess its place in the universe.

While astronomers have found a number of exoplanets over the last few years that share one or two key traits with our own world — such as size or inferred surface temperature — they have yet to bag a bona fide "alien Earth." But that should change in 2013, scientists say.

"I'm very positive that the first Earth twin will be discovered next year," said Abel Mendez, who runs the Planetary Habitability Laboratory at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo.

Planets piling up

Astronomers discovered the first exoplanet orbiting a sunlike star in 1995. Since they, they've spotted more than 800 worlds beyond our own solar system, and many more candidates await confirmation by follow-up observations. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

NASA's prolific Kepler Space Telescope, for example, has flagged more than 2,300 potential planets since its March 2009 launch. Only 100 or so have been confirmed to date, but mission scientists estimate that at least 80 percent will end up being the real deal.

The first exoplanet finds were scorching-hot Jupiter-like worlds that orbit close to their parent stars, because they were the easiest to detect. But over time, new instruments came online and planet hunters honed their techniques, enabling the discovery of smaller and more distantly orbiting planets — places more like Earth.

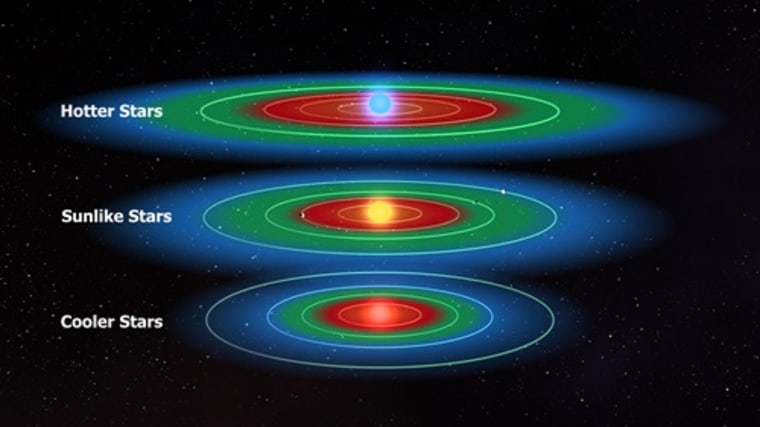

Last December, for instance, Kepler found a planet 2.4 times larger than Earth orbiting in its star's habitable zone — that just-right range of distances where liquid water, and perhaps life as we know it, can exist.

The Kepler team and other research groups have detected several other worlds like that one (which is known as Kepler-22b), bringing the current tally of potentially habitable exoplanets to nine by Mendez' reckoning.

Zeroing in on Earth's twin

None of the worlds in Mendez' Habitable Exoplanets Catalog is small enough to be a true Earth twin. The handful of Earth-size planets spotted to date all orbit too close to their stars to be suitable for life. [Gallery: 9 Potentially Habitable Exoplanets]

But it's only a matter of time before a small, rocky planet is spotted in the habitable zone — and Mendez isn't the only researcher who thinks that time is coming soon.

"The first planet with a measured size, orbit and incident stellar flux that is suitable for life is likely to be announced in 2013," said Geoff Marcy, a veteran planet hunter at the University of California at Berkeley and a member of the Kepler team.

Mendez and Marcy both think this watershed find will be made by Kepler, which spots planets by flagging the telltale brightness dips caused when they pass in front of their parent stars from the instrument's perspective.

Kepler needs to witness three of these "transits" to detect a planet, so its early discoveries were tilted toward close-orbiting worlds (which transit more frequently). But over time, the telescope has been spotting more and more distantly orbiting planets — including some in the habitable zone.

An instrument called HARPS (short for High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) is also a top contender, having already spotted a number of potentially habitable worlds. HARPS, which sits on the European Southern Observatory's 3.6-meter telescope in Chile, allows researchers to detect the tiny gravitational wobbles that orbiting planets induce in their parent stars.

"HARPS should be able to find the most interesting and closer Earth twins," Mendez told Space.com via email, noting that many Kepler planets are too far away to characterize in detail. "A combination of its sensitivity and long-term observations is now paying off."

And there are probably many alien Earths out there to be found in our Milky Way galaxy, researchers say.

"Estimating carefully, there are 200 billion stars that host at least 50 billion planets, if not more," Mikko Tuomi, of the University of Hertfordshire in England, told Space.com via email.

"Assuming that 1:10,000 are similar to the Earth would give us 5,000,000 such planets," added Tuomi, who led teams reporting the discovery of several potentially habitable planet candidates this year, including an exoplanet orbiting the star Tau Ceti just 11.9 light-years from Earth. "So I would say we are talking about at least thousands of such planets."

What it would mean

Whenever the first Earth twin is confirmed, the discovery will likely have a profound effect on humanity.

"We humans will look up into the night sky, much as we gaze across a large ocean," Marcy told Space.com via email. "We will know that the cosmic ocean contains islands and continents by the billions, able to support both primitive life and entire civilizations."

Marcy hopes such a find will prod our species to take its first real steps beyond its native solar system.

"Humanity will close its collective eyes, and set sail for Alpha Centauri," Marcy said, referring to the closest star system to our own, where an Earth-size planet was discovered earlier this year.

"The small steps for humanity will be a giant leap for our species. Sending robotic probes to the nearest stars will constitute the greatest adventure we Homo sapiens have ever attempted," Marcy added. "This massive undertaking will require the cooperation and contribution from all major nations around world. In so doing, we will take our first tentative steps into the cosmic ocean and enhance our shared sense of purpose on this terrestrial shore."

Follow Space.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or Space.com . We're also on Facebook and