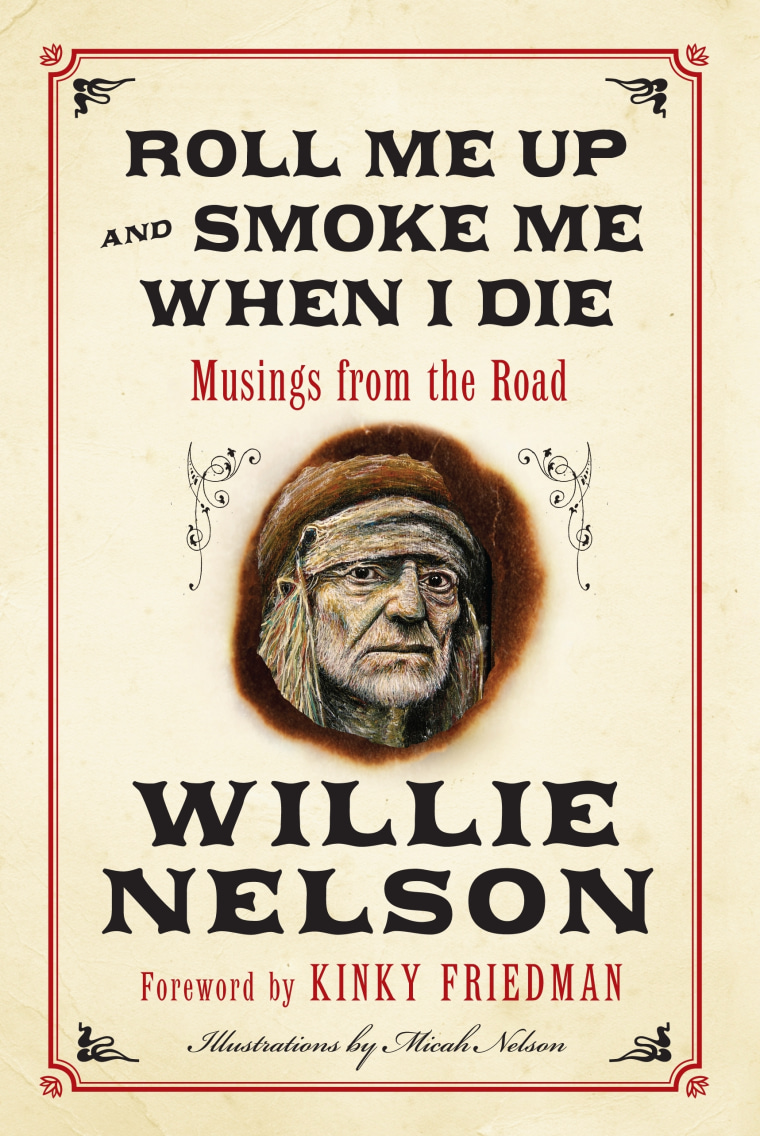

Country music legend Willie Nelson tells his side of the story in “Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die,” detailing the fabled outlaw’s notorious past, his timeless music and his outlook on life. Here’s an excerpt.A Better Way to Make a Buck

One day while I was picking cotton, on a farm by the highway that ran between Abbott and Hillsboro—it was about a hundred degrees in the hot Texas sun, and there I was pulling along a sack of cotton—a Cadillac came by with its windows rolled up. There was something about that scene that made me start thinking more about playing a guitar. Here I was picking cotton in the heat and thinking, There’s a better way to make a dollar, and a living, than picking cotton. Sister Bobbie and I picked cotton on all the farms around Abbott every summer and every day after school. In Abbott, the schools let out at noon during harvest season, so we could all work in the fields. That’s how we made our extra money. I did a lot more farmwork than Sister Bobbie, things like baling hay and working in the cotton gin and on the corn sheller, all of which was very hard work but in a lot of ways was good for me because it made me work harder on my guitar.

My next-door neighbor was Mrs. Bressler, a devout Christian lady who was very good friends with my grandmother. They lived next door to each other in Abbott all the time I was growing up there. She told me when I was about six years old that anyone who drank beer or smoked cigarettes—anyone who used alcohol or tobacco, really—was “going to hell.” She really believed that, and for a while I did too. I had started drinking and smoking by the time I was six years old, so if that was true, I’ve been hell-bound since I was barely out of kindergarten! I would take a dozen eggs from our chicken, walk to the grocery store, and trade the dozen eggs for a pack of Camel cigarettes. I liked the little camel on the package—after all, I was only six. They were marketing directly to me! After that I liked Lucky Strikes, Chesterfields, even tried the menthol cigarettes, because they said it was a lot easier on your throat. That’s a lot of horses__t. Cigarettes killed my mother, my father, my stepmother, and my stepfather—half the people in my family were killed by cigarettes. I watched my dad die after lying in bed with oxygen the last couple of years of his life. Cigarettes have killed more people than all the wars put together I think. But like my old buddy Billy Cooper used to say, “It’s my mouth. I’ll haul coal in it if I want to.” I think I’d have been better off with the coal.

I tried a hundred times to quit smoking. By the time I actually did quit smoking cigarettes, I had already started smoking pot, which I picked up from a couple of old musician buddies that I had run into in Fort Worth. The first time I smoked pot I kept waiting for something to happen. I kept puffing and puffing, waiting for something to happen, but nothing happened. So I went back to cigarettes and whiskey, which made s__t happen. As I started playing the clubs around Texas, I ran into the pills: the white crosses, the yellow turnarounds, and the black mollies. I never liked any of the pills or speed, because I didn’t need speed; I was already speeding. So I quit everything but pot. Cigarettes were the hardest. My lungs were killing me from smoking everything from cedar post to grapevine, but I wasn’t getting high off the cigarettes, so it was good-bye, Chesterfields, and I haven’t smoked since. It’s one of the best decisions I have ever made.

The day I quit, the day that I decided that I was through with f__ing cigarettes, I took out the pack of cigarettes that I had just bought, opened it, threw them all away, rolled up twenty joints, replaced the twenty Chesterfields, and put the pack back in my shirt pocket, where I always kept my cigarettes, because half of the habit, for me, was reaching for and lighting something.

The Night Owl and Bud Fletcher

The Night Owl was hell—at least that’s what Mrs. Bressler told me. It was the first place that my best friend, Zeke Varnon, and I used to hang out, get drunk, and play music. There was a lot of drinking, smoking, dancing, cussing, and fighting. Margie and Lundy ran the Night Owl. In the middle of all this confusion and fighting was music. It’s what brought everyone there. It was one of the first beer joints that I played. Me, Sister Bobbie, Whistle Watson, and a little harelipped drummer. Bud Fletcher, who was Sister Bobbie’s husband—she married him while she was a senior in high school—was a very good friend of mine. He was my first promoter/booker. He was about half hustler. We had a band called “Bud Fletcher and the Texans.” We played the Night Owl, Chief Edwards, the Bloody Bucket, and every beer joint in Texas at least once. Bud was the bandleader, but he was not a musician, even though he looked like he was. He was in the band with us and he played upright bass. Well, not really played it. He spun it and kicked it a lot, but I never heard one note of music come out of it.

I would always hock my guitar during the week at a pawnshop in Waco and drink and gamble up all the money, and Bud would always have to go get my guitar out of hock before the weekend so we could go play our music gigs. I used to say I hocked my guitar so many times that the pawnbroker played it better than I did. But Bud would always get it out of hock, because he would have already booked us in a place, and we needed to go play.

From , by Willie Nelson. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2012 by Willie Nelson.