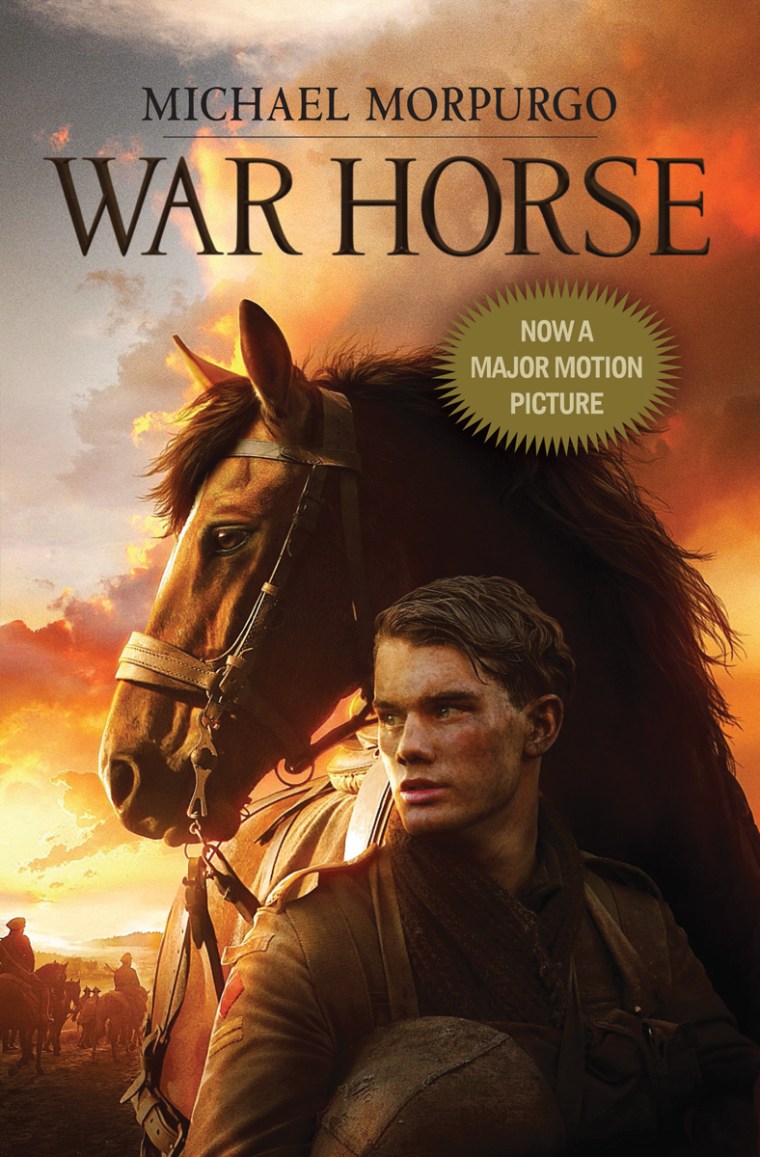

Stricken by hard times, young Albert's father is forced to sell his son's beloved horse to the army to support their farm. Joey the horse does not understand at first, but soon learns that his life now involves serving the cavalry. Albert, meanwhile, vows to be reunited with his childhood friend. In Michael Morpurgo's "War Horse," loyalty and friendship struggle to sustain against the tides of war. Here's an excerpt.

An officer pushed through the crowd toward us. He was tall and elegant in his jodhpurs and military belt, with a silver sword at his side. He shook Albert’s father by the hand. “I told you I’d come, Captain Nicholls, sir,” said Albert’s father. “It’s because I need the money, you understand. Wouldn’t part with a horse like this ’less I had to.”

“Well, Farmer,” said the officer, nodding his appreciation as he looked me over. “I’d thought you’d be exaggerating when we talked in The George last evening. ‘Finest horse in the parish,’ you said, but then everyone says that. But this one is different — I can see that.” And he smoothed my neck gently and scratched me behind my ears. Both his hand and his voice were kind, and I did not shrink away from him. “You’re right, Farmer. He’d make a fine mount for my regiment and we’d be proud to have him — I wouldn’t mind using him myself. No, I wouldn’t mind at all. If he turns out to be all he looks, then he’d suit me well enough. Fine-looking animal, no question about it.”

“Forty pounds you’ll pay me, Captain Nicholls, like you promised yesterday?” Albert’s father said in a voice that was unnaturally low, almost as if he did not want to be heard by anyone else. “I can’t let him go for a penny less. A man’s got to live.”

“That’s what I promised you last evening, Farmer,” Captain Nicholls said, opening my mouth and examining my teeth. “He’s a fine young horse — strong neck, sloping shoulder, straight fetlocks. Done much work has he? Have you taken him hunting?”

“My son rides him every day,” said Albert’s father. “He tells me that he goes like a racer and jumps like a hunter.”

“Well,” said the officer, “as long as our vet passes him as fit and sound in wind and limb, you’ll have your forty pounds, as we agreed.”

“I can’t be long, sir,” Albert’s father said, glancing back over his shoulder. “I have to get back. I have my work to see to.”

“Well, we’re busy recruiting in the village as well as buying,” said the officer. “But we’ll be as quick as we can for you. True, there’s a lot more good men volunteers than there are good horses in these parts, and the vet doesn’t have to examine the men, does he? You wait here, I’ll only be a few minutes.”

Captain Nicholls led me away through the archway opposite the pub and into a large yard where there were men in white coats and a uniformed clerk sitting down at a table taking notes. I thought I heard old Zoey calling after me, so I shouted back to reassure her for I felt no fear at this moment. I was too interested in what was going on around me. The officer talked to me gently as we walked away, so I went along almost eagerly. The vet, a small, bustling man with a bushy black moustache, prodded me all over, lifted each of my feet to examine them — which I objected to — and then peered into my eyes and my mouth, sniffing at my breath. Then I was trotted around and around the yard before he pronounced me a perfect specimen. “Sound as a bell. Fit for anything, cavalry or artillery,” were the words he used. “No splints, not lame, good feet and teeth. Buy him, Captain,” he said. “He’s a good one.”

I was led back to Albert’s father who took the offered money from Captain Nicholls, stuffing it quickly into his trouser pocket. “You’ll look after him, sir?” he said. “You’ll see he comes to no harm? My son’s very fond of him, you see.” He reached out and brushed my nose with his hand. There were tears filling his eyes. At that moment he became almost a likable man to me. “You’ll be all right, old son,” he whispered to me. “You won’t understand and neither will Albert, but unless I sell you, I can’t keep up with the mortgage and we’ll lose the farm. I’ve treated you bad — I’ve treated everyone bad. I know it and I’m sorry for it.” And he walked away from me, leading Zoey behind him. His head was lowered, and he looked suddenly like a shrunken man.

It was then that I fully realized I was being abandoned, and I began to neigh, a high-pitched cry of pain and anxiety that shrieked out through the village. Even old Zoey, obedient and placid as she always was, stopped and would not be moved on no matter how hard Albert’s father pulled her. She turned, tossed up her head, and shouted her farewell. But her cries became weaker and she was finally dragged away and out of my sight. Kind hands tried to contain me and to console me, but I was inconsolable.

I had just about given up all hope, when I saw my Albert running toward me through the crowd, his face red with exertion. The band had stopped playing, and the entire village looked on as he came up to me and put his arms around my neck.

“He’s sold him, hasn’t he?” he said quietly, looking up at Captain Nicholls who was holding me. “Joey is my horse. He’s my horse and he always will be, no matter who buys him. I can’t stop my father from selling him, but if Joey goes with you, I go. I want to join up and stay with him.”

“You’ve got the right spirit for a soldier, young man,” said the officer, taking off his peaked cap and wiping his brow with the back of his hand. He had black curly hair and a kind, open look on his face. “You’ve got the spirit, but you haven’t got the years. You’re too young and you know it. Seventeen’s the youngest age we take. Come back in a year or so and then we’ll see.”

“I look seventeen,” Albert said, almost pleading. “I’m bigger than most seventeen-year-olds.” But even as he spoke, he could see he was getting nowhere. “You won’t take me then, sir? Not even as a stable boy? I’ll do anything — anything.”

“What’s your name, young man?” Captain Nicholls asked.

“Narracott, sir, Albert Narracott.”

“Well, Mr. Narracott. I’m sorry I can’t help you.” The officer shook his head and replaced his cap. “I’m sorry, young man, regulations. But don’t you worry about your Joey. I shall take good care of him until you’re ready to join us. You’ve done a fine job with him. You should be proud of him — he’s a fine, fine horse, but your father needed the money for the farm, and a farm won’t run without money. You must know that. I like your spirit, so when you’re old enough, you must come and join the cavalry. We need men like you, and it will be a long war I fear, longer than people think. Mention my name. I’m Captain Nicholls, and I’d be proud to have you with us.”

“There’s no way, then?” Albert asked. “There’s nothing I can do?”

“Nothing,” said Captain Nicholls. “Your horse belongs to the army now, and you’re too young to join up. Don’t you worry — we’ll look after him. I’ll take personal care of him, and that’s a promise.”

Albert rubbed my nose for me as he often did and stroked my ears. He was trying to smile but could not. “I’ll find you again, you old silly,” he said quietly. “Wherever you are, I’ll find you, Joey. Take good care of him, please, sir, till I find him again. There’s not another horse like him, not in the whole world — you’ll find that out. Say you promise?”

“I promise,” said Captain Nicholls. “I’ll do everything I can.” And Albert turned and went away through the crowd until I could see him no more.

From "War Horse" by Michael Morpurgo. Scholastic Inc. Copyright (c) 1982 by Michael Morpurgo. Reprinted by permission.