Radiation is spewing from damaged reactors at a crippled nuclear power plant in tsunami-ravaged northeastern Japan in a dramatic escalation of the 4-day-old catastrophe. The prime minister has warned residents to stay inside or risk getting radiation sickness.

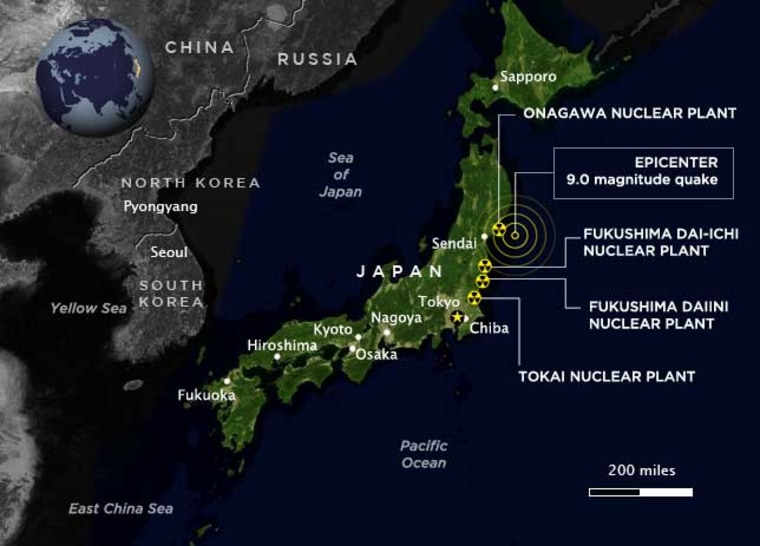

In a nationally televised statement, Prime Minister Naoto Kan said radiation has spread from the three reactors of the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant in one of the hardest-hit provinces in Friday's 9.0-magnitude earthquake and the ensuing tsunami. He told people living within 12 miles (20 kilometers) of the plant to evacuate and those within 19 miles (30 kilometers) to stay indoors.

"The level seems very high, and there is still a very high risk of more radiation coming out," Kan said.

Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said early Tuesday that a fourth reactor at the Fukushima Dai-ichi complex was on fire and that more radiation was released, but officials announced later in the day that the fire was extinguished.

"Now we are talking about levels that can damage human health. These are readings taken near the area where we believe the releases are happening. Far away, the levels should be lower," Edano said.

A third explosion in four days rocked the earthquake-damaged plant earlier Tuesday.

Two sources told NBC News' Robert Bazell that the blast breached the containment structure and that radiation had leaked out.

Japan's nuclear agency said the explosion may have damaged the reactor's suppression chamber, a water-filled tube at the bottom of the container that surrounds the nuclear core, said agency spokesman, Shinji Kinjo. He said that chamber is part of the container wall.

The suppression chamber is used to turn steam back into water to cool the reactor and also plays a role in removing radioactive particles from the steam.

Rising radiation levels

Japanese officials had previously said radiation levels at the plant were within safe limits, and international scientists said that while there were serious dangers, there was little risk of a catastrophe like Chernobyl in Ukraine, where the reactor exploded and released a radiation cloud over much of Europe.

Unlike the plant in Japan, the Chernobyl reactor was not housed in a sealed container to prevent the release of radiation.

Radiation levels measured at the front gate of the Dai-ichi plant spiked following Tuesday's explosion, Kinjo said.

Detectors showed 11,900 microsieverts of radiation three hours after the blast, up from just 73 microsieverts beforehand, Kinjo said. He said there was no immediate health risk because the higher measurement was less radiation that a person receives from an X-ray. He said experts would worry about health risks if levels exceed 100,000 microsieverts.

In Tokyo, slightly higher-than-normal radiation levels were detected Tuesday but officials insisted there are no health dangers.

"The amount is extremely small, and it does not raise health concerns. It will not affect us," Takayuki Fujiki, a Tokyo government official said.

In a sign of mounting fears about the risk of radiation, neighboring China said it was strengthening monitoring and Air China said it had canceled flights to Tokyo.

Several embassies advised staff and citizens to leave affected areas. Tourists cut short vacations and multinational companies either urged staff to leave or said they were considering plans to move outside the city.

The blast at Dai-ichi Unit 2 followed two hydrogen explosions at the plant — the latest on Monday — as authorities struggled to prevent the catastrophic release of radiation in the area devastated by a tsunami.

The troubles at the Dai-ichi complex began when Friday's massive quake and tsunami in Japan's northeast knocked out power, crippling cooling systems needed to keep nuclear fuel from melting down.

Officials said 50 workers were still there trying to put water into the reactors to cool them. They say 800 other staff were evacuated. The fires and explosions at the reactors have injured 15 workers and military personnel and exposed up to 190 people to elevated radiation.

The latest explosion came as Japanese engineers pumped seawater into Unit 2 of the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant after coolant water levels there dropped, exposing uranium fuel rods.

The water drop left the rods no longer completely covered in coolant, thus increasing the risk of a radiation leak and the potential for a meltdown at the Unit 2 reactor, Tokyo Electric Power Co. said.

3 reactors 'likely' melting

Workers managed to raise water levels after the second drop Monday night, but they began falling for a third time, according to Naoki Kumagai, an official with Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Agency.

It now seems that the nuclear fuel rods inside all three functioning reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi complex are melting, a senior government official said.

"Although we cannot directly check it, it's highly likely happening," Edano said.

Some experts would consider melting fuel rods a partial meltdown. Others, though, reserve that term for times when nuclear fuel melts through a reactor's innermost chamber but not through the outer containment shell.

Officials held out the possibility that, too, may be happening. "It's impossible to say whether there has or has not been damage" to the vessels, Kumagai said.

If a complete reactor meltdown — where the uranium core melts through the outer containment shell — were to occur, a wave of radiation would be released, resulting in major, widespread health problems.

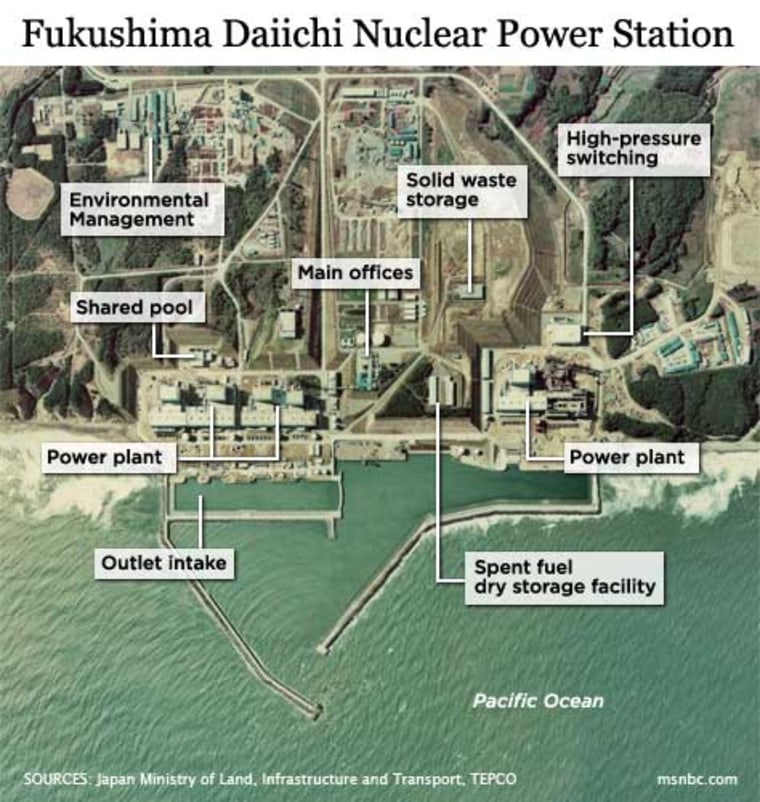

Also unknown was the status of any nuclear waste that might be stored at the site, and whether the pools housing used fuel were still being cooled to prevent a radiation release.

The cabinet secretary's comments followed a hydrogen explosion at Unit 3 on Monday that injured 11 workers and was heard 25 miles away. A similar explosion happened at Unit 1 on Saturday.

Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan later said the government was setting up a joint response headquarters with TEPCO to better manage the crisis.

Of all these troubles, the drop in water levels at Unit 2 had officials the most worried.

"Units 1 and 3 are at least somewhat stabilized for the time being," said Nuclear and Industrial Agency official Ryohei Shiomi. "Unit 2 now requires all our effort and attention."

The blast occurred as authorities tried to cool the reactor with seawater.

"It's like a horror movie," said 49-year-old Kyoko Nambu as she stood on a hillside overlooking her ruined hometown of Soma, about 25 miles from the plant. "Our house is gone and now they are telling us to stay indoors.

"We can see the damage to our houses, but radiation? ... We have no idea what is happening. I am so scared."

Authorities said operators knew an explosion was a possibility as they struggled to reduce pressure inside the reactor containment vessel, but apparently felt they had no choice if they wanted to avoid a complete meltdown. In the end, the hydrogen in the released steam mixed with oxygen in the atmosphere and set off the blast.

In some ways, the explosion at Unit 3 was not as dire as it might seem.

The blast actually lessened pressure building inside the troubled reactor, and officials said the all-important containment shell — thick concrete armor around the reactor — had not been damaged. In addition, officials said radiation levels remained within legal limits, though anyone left within 12 miles of the scene was ordered to remain indoors.

"We have no evidence of harmful radiation exposure" from Monday's blast, Deputy Cabinet Secretary Noriyuki Shikata told reporters.

On Saturday, a similar explosion took place at the plant's Unit 1, injuring four workers and causing mass evacuations. A Japanese official said 22 people had been confirmed to have suffered radiation contamination and up to 190 may have been exposed. Workers in protective clothing used hand-held scanners to check people arriving at evacuation centers.

While four Japanese nuclear complexes were damaged in the wake of Friday's twin disasters, the Dai-ichi complex, which sits just off the Pacific coast and was badly hammered by the tsunami, has been the focus of most of the worries over Japan's deepening nuclear crisis. All three of the operational reactors at the complex now have faced severe troubles.

The length of time since the nuclear crisis began could indicate that the chemical reactions inside the reactors were not moving quickly toward a complete meltdown.

"We're now into the fourth day. Whatever is happening in that core is taking a long time to unfold," said Mark Hibbs, a senior associate at the nuclear policy program for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "They've succeeded in prolonging the timeline of the accident sequence."

He noted, though, that Japanese officials appeared unable to figure out what was going on deep inside the reactors. In part, that was probably because of the damage done to the facility by the tsunami.

"The real question mark is what's going on inside the core," he said.

The U.N. World Health Organization said the public health risk from Japan's atomic plants remained "quite low."

Moreover, the Japan Meteorological Agency said that the winds in the area were blowing toward the Pacific Ocean, away from populated areas.

'Fundamentally different' from Chernobyl

Citing experts, that radioactive steam could be released from the stricken plants for weeks or possibly months.

The Fukushima Dai-ichi complex was due to be decommissioned in February but was given a new 10-year lease on life.

Its reactors were designed by General Electric. (Msnbc.com is a joint venture between NBC Universal and Microsoft. GE is a part owner of NBC Universal.)

Japanese authorities have classified the event at Dai-ichi's No. 1 reactor as a level 4 "accident with local consequences" on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES).

The scale is used to consistently communicate the safety significance of events associated with sources of radiation. The scale runs from 0 (deviation — no safety significance) to 7 (major accident).

The 1979 Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania was a level 5 ("accident with wider consequences"). The 1986 Chernobyl disaster was a level 7.

The reactor that exploded at Chernobyl, sending a cloud of radiation over much of Europe and killing 4,000 either directly or from cancer, was not housed in a sealed container as those at Dai-ichi are. The Japanese reactors also do not use graphite, which burned for several days at Chernobyl.

Prime Minister Kan on Sunday sought to allay radiation fears. "Radiation has been released in the air, but there are no reports that a large amount was released," Jiji news agency quoted him as saying. "This is fundamentally different from the Chernobyl accident."

Japan's nuclear crisis was triggered by twin disasters on Friday, when the most powerful earthquake in the country's recorded history was followed by a tsunami that savaged its northeastern coast with breathtaking speed and power.

Japan has a total of 55 reactors spread across 17 complexes nationwide.

U.S. sailors exposed

On Monday, the U.S. Seventh Fleet moved its ships and aircraft away from Japan's northeast coast after discovering low-level radioactive contamination on crews returning from relief missions.

The fleet said that the radiation was from a plume of smoke and steam released from the crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi plant.

Seventeen U.S. military personnel involved in helicopter relief missions were found to have been exposed to low levels of radiation upon returning to the USS Ronald Reagan, an aircraft carrier about 100 miles offshore.

U.S. officials said the level was roughly equal to one month's normal exposure to natural background radiation in the environment, and after scrubbing with soap and water, the 17 were declared contamination-free.

As for the potential of radiation reaching the U.S. mainland, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission on Sunday said no harmful levels were likely.

"Given the thousands of miles between the two countries, Hawaii, Alaska, the U.S. territories and the U.S. West Coast are not expected to experience any harmful levels of radioactivity," it said in a statement.

In other developments Monday:

- India announced a review of all nuclear reactors in the country in view of the Japanese radiation leak. India has 20 nuclear power plants, mostly located along the coast.

- Germany's coalition government has suspended an agreement prolonging the life of the nation's nuclear power stations, Chancellor Angela Merkel said.

- Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin said Russia would not change ambitious plans to build dozens of nuclear power stations in coming decades.

- The Swiss government suspended plans to replace and build new nuclear plants pending a review of the two hydrogen explosions at Japanese plants.