An official with Japan's nuclear safety commission says that a meltdown at a nuclear power plant affected by the country's massive earthquake is possible.

Ryohei Shiomi said Saturday that officials were checking whether a meltdown had taken place at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, which had lost cooling ability in the aftermath of Friday's powerful earthquake.

If the fuel rods melted or are melting, a breach could develop in the nuclear reactor vessel and the question then becomes one of how strong the containment structure around the vessel is and whether it has been undermined by the earthquake, experts said.

Shiomi said that even if there was a meltdown, it wouldn't affect humans outside a six-mile (10-kilometer) radius.

Japan earlier Saturday declared states of emergency for five nuclear reactors at two power plants after the units lost cooling ability in the aftermath of Friday's powerful earthquake. Thousands of residents were evacuated as workers struggled to get the reactors under control to prevent meltdowns.

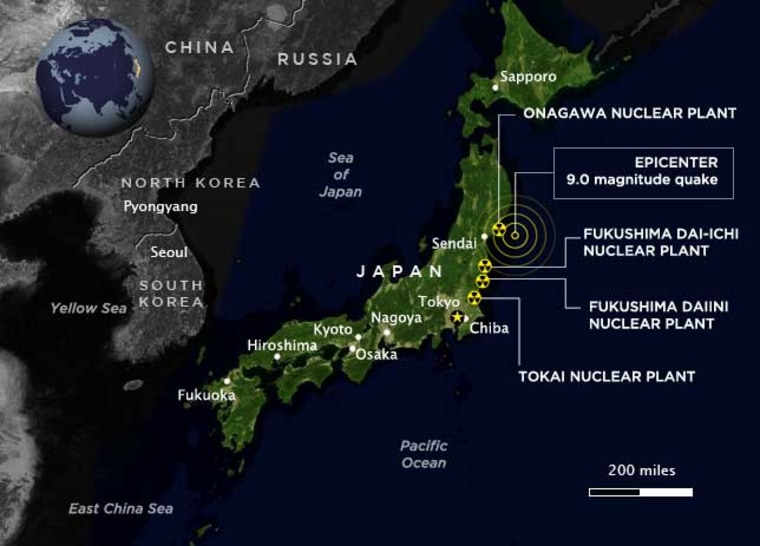

Operators at the Fukushima Daiichi plant's Unit 1 scrambled ferociously to tamp down heat and pressure inside the reactor after the 8.9 magnitude quake and the tsunami that followed cut off electricity to the site and disabled emergency generators, knocking out the main cooling system.

Some 3,000 people within two miles (three kilometers) of the plant were urged to leave their homes, but the evacuation zone was more than tripled to 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) after authorities detected eight times the normal radiation levels outside the facility and 1,000 times normal inside Unit 1's control room.

The government declared a state of emergency at the Daiichi unit — the first at a nuclear plant in Japan's history. But hours later, the Tokyo Electric Power Co., which operates the six-reactor Daiichi site, announced that it had lost cooling ability at a second reactor there and three units at its nearby Fukushima Daini site.

The government quickly declared states of emergency for those units, too, and thousands of residents near Fukushima Daini also were told to leave.

Japan's nuclear safety agency said the situation was most dire at Fukushima Daiichi's Unit 1, where pressure had risen to twice what is consider the normal level. The International Atomic Energy Agency said in a statement that diesel generators that normally would have kept cooling systems running at Fukushima Daiichi had been disabled by tsunami flooding.

Officials at the Daiichi facility began venting radioactive vapors from the unit to relieve pressure inside the reactor case. The loss of electricity had delayed that effort for several hours.

Plant workers there labored to cool down the reactor core, but there was no prospect for immediate success. They were temporarily cooling the reactor with a secondary system, but it wasn't working as well as the primary one, according to Yuji Kakizaki, an official at the Japanese nuclear safety agency.

TEPCO said the boiling water reactors shut down at about 2:46 p.m. local time following the earthquake due to the loss of offsite power and the malfunction of one of two off-site power systems. That triggered emergency diesel generators to startup and provide backup power for plant systems.

About an hour after the plant shut down, however, the emergency diesel generators stopped, leaving the units with no power for important cooling functions.

Nuclear plants need power to operate motors, valves and instruments that control the systems that provide cooling water to the radioactive core.

The race to restore the reactors’ cooling systems before the radioactive fuel was damaged sent ripples of concern across Pacific, where scientists on both sides of the U.S. debate over the safety of nuclear power acknowledged that the company was facing a serious situation.

Edwin Lyman, a senior scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, which opposes nuclear energy, told msnbc.com that TEPCO was facing a potential catastrophe.

'It's just as bad as it sounds' “It’s just as bad as it sounds,” he said. “What they have not been able to do is restore cooling of the radioactive core to prevent overheating and that’s causing a variety of problems, including a rise in temperature and pressure with the containment (buildings).

“What’s critical is, are they able to restore cooling and prevent fuel damage? If the fuel starts to get damaged, eventually it will melt through the reactor vessel and drop to the floor of the containment building,” raising the odds that highly radioactive materials could be released into the environment.

But Steve Kerekes, spokesman for the U.S.-based Nuclear Energy Institute, said that while the situation was serious, a meltdown remains unlikely and, even if it occurred would not necessarily pose a threat to public health and safety.

“Obviously that wouldn’t be a good thing, but at Three Mile Island about half the core melted and, at the end of the day … there were no adverse impacts to the public,” he said.

Experts also downplayed the seriousness of the trace levels of radiation detected at the Fukushima Daiichi plant.

Japan’s Asahi Shimbum newspaper reported that radiation levels per hour in the area near the front entrance of the No. 1 Fukushima plant reached 0.59 micro Sievert, which is eight times the normal levels. The central control room of the reactor recorded radiation levels 1,000 times the normal level, which would be approximately 70 microsieverts per hour, or 7 millirems, according to calculations by msnbc.com.

Health effects unlikely Generally it would take much higher levels of outside exposure to cause health problems in humans. Radiation exposure is often measured in units called “millirem,” which is 1/1000 of a rem. The average American is exposed to about 620 millirem each year, with about half from natural sources and half from manmade sources, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Exposures of less than 50 millirem typically produce changes in blood chemistry, but no symptoms, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

By comparison, normal exposure rates range from approximately 0.03 microsieverts per hour to 0.23 microsieverts per hour in La Paz, Bolivia, the highest city in the world.

Average U.S. exposure to all sources of radiation is 360 millirems per year, with 300 millirems from natural sources. A chest X-ray results in an exposure of about 8 to 10 millirems per film. A cross-country airplane flight results in a dose of 4 millirems.

Dr. Fred Mettler, emeritus professor of radiology at the University of New Mexico, studied the health effects of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant explosions in Ukraine and has spent decades researching and writing about radiation exposure.

Mettler said the plants in the U.S. and Japan are far advanced from Chernobyl, which he likened to an airplane hangar with the nuclear reactor core sitting out in the open.

Japanese scientists have had more than 60 years since World War II to study the health effects of radiation poisoning and they won't take any step lightly, including releasing radioative vapors into the atmosphere to ease building pressure in a reactor, he said.

"These people are more knowledgeable about radiation than anyone," Mettler said.

"People don't become acutely sick until they're over 50 rem and more like 100 rem," Mettler said.

However, he noted that Japanese scientists studying health effects since Hiroshima have determined that some health effects can start to occur at exposures of 15 rem, even if the results aren't apparent for 10 years.

There were about 80,000 survivors of the atomic bomb, for instance, with an average exposure of 23 rem, Mettler said. During the next 50 years about 9,000 of those survivors died of cancer. However, Japanese scientists concluded that the toll included about 500 excess deaths, that is, deaths that would not otherwise have been expected.

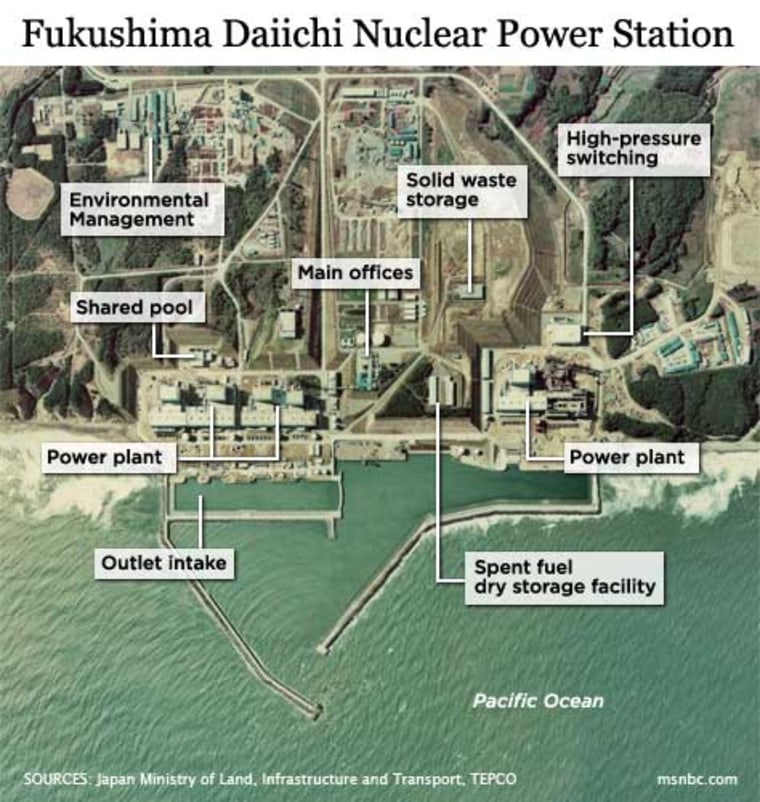

The Daiichi site is located in Onahama city, about 170 miles (270 kilometers) northeast of Tokyo. The 460-megawatt Unit 1 began operating in 1971 and is the oldest at the site. It is a boiling water reactor that drives the turbine with radioactive water, unlike pressurized water reactors usually found in the United States. Japanese regulators decided in February to allow it to run another 10 years.

U.S. President Barack Obama said he spoke with Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan earlier Friday, and that the Japanese leader told him there were no radiation leaks from Japan's nuclear power plants.

"Right now our Department of Energy folks are in direct contact with their counterparts in Japan and are closely monitoring the situation," a senior administration official who handles nuclear issues told NBC News. "So far the government of Japan has not asked for any specific assistance with regard to the nuclear plant, but DOE and other U.S. government agencies are assessing the role they could play in any response and stand by to assist if asked."

Japan has a "tremendous amount of technical capability and resources" to respond to the issue themselves for now, sources told NBC News.

Meanwhile, new power supply cars to provide emergency electricity for systems that failed at the Fukushima-Daiichi plant have arrived there, the World Nuclear Association said.

"The World Nuclear Association understands that three to four power supply cars have arrived and that additional power modules are being prepared for connection to provide power for the energy cooling system," said Jeremy Gordon, analyst at the London-based WNA.

The cables were being set up to supply emergency power. Other power modules were in transit by air, WNA added on its website.