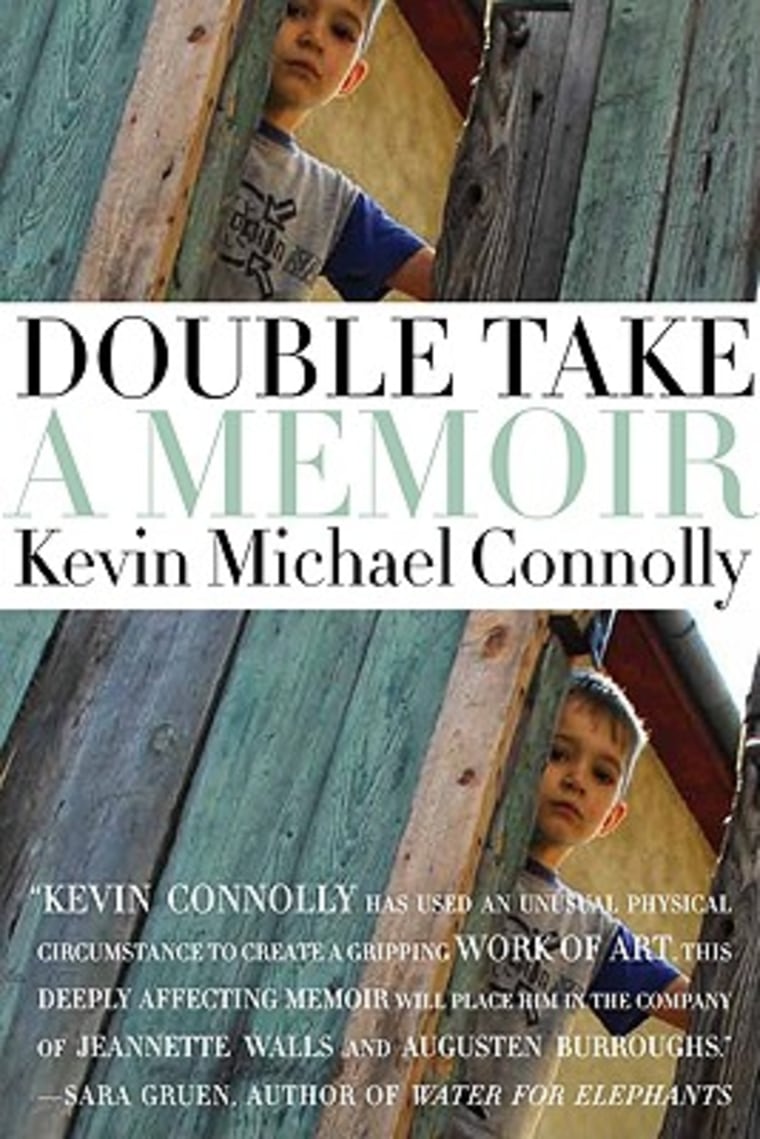

Photographer, champion skier and skateboarder Kevin Connolly, 24, was born without legs. But that hasn’t stopped the Montana native from traveling through 17 countries and taking more than 30,000 pictures to capture the stares from strangers — and writing about it all. Here is an excerpt from chapter one of “Double Take,” Connolly’s memoir.

Chapter one: Birth Day Melnik, Czech Republic

“You were an exclamation point on a really tough couple of years,” is what my mom says about my birth.

I am calling my mother from my apartment in Bozeman, to ask her about something I’ve always wanted to know but have been a little reluctant to delve into. Up until now, I’d always avoided asking too much about the time directly following my birth for fear that it might bring back feelings neither of us wanted to deal with again.

But first we must have the obligatory talk about Montana’s mercurial spring weather. After a week of blizzards and deliriously frigid temperatures, the cold had let up long enough for the snow to turn into a brown goulash of dirt and ice. It’s the time of year when most people become homebodies, seeking anything that is warm and dry.

Except, as Mom quickly tells me, a good portion of our home is now submerged in water. Earlier in the day, a pipe had sprung a leak and had emptied gallons into the kitchen, soaking through the floorboards and down into the basement.

“The kitchen is totally flooded. The whole floor is going to have to be replaced.”

She sighs, then laughs.

“Oh well. Been through worse.”

I imagine the kitchen, swollen and bloated, weeping out the old mold and dust of our family’s history. I know that Mom and Dad will patch it back together themselves, and Dad confirms my speculation by yelling over Mom that he’s going to the hardware store later. He’s already had a couple of beers, by the sound of his laugh.

My parents don’t have much money; they never did. There is a picture in the entryway that shows our house in the state that my parents first purchased it. Weeds that came up to my head (three feet, one inch, incidentally) made up the front yard and lined a dirt ditch, driveway, and road. The ranch house five miles outside Helena cost $2,000; in 1984, it was what they could afford.

They purchased the house a year before I was born, in the midst of a run of family disasters. Mom’s sister, Mickey, had been diagnosed with brain cancer; by the time of my mom’s pregnancy, she had become terminally ill. A single mother with four kids, she asked my mom to take custody of her children. She died in March when Mom was four months pregnant with me.

Even before Mickey passed away, Mom had started attending court hearings to decide who was to get custody of her children: my parents or Mickey’s ex-husband. As my mom’s stomach grew, so did the question of whether she would be caring for one child or five.

As Mom split her time between court and visits to her sister in the nursing home, her father was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Shortly thereafter, her mother was diagnosed with skin cancer. It seemed impossible to have this much bad luck all at once.

Recalling all this, Mom pauses for a moment. I imagine her sitting in the living room with blue carpet under her feet. The smell of water and rotting wood emanating from the kitchen. The sound of Dad’s television upstairs. Our golden retriever, Tuck, in the entryway. Frost on the windows and the dim light of sixty-watt bulbs filling the interior. Lining up her thoughts before letting them all out in one rushed breath. I finally hear her exhale, slowly.

“There were two sides to this stretch of time. My personality is pretty resilient, but there was so much going on: my mom and dad getting cancer, Mickey dying, fighting for her kids … it was hard not to get down. The one positive in all of this was my pregnancy. We’d been married for three years, and your dad and I really wanted a baby. So we were leaning pretty heavily on the excitement of having our first kid.”

I listen on the other end of the line, knowing how the story ends, thinking about the crisis my birth must have been.

The final surprise began on August 17 around six in the morning. Sleeping in their old waterbed, my mom woke up in a puddle, her nightgown drenched.

“Brian, I think the bed broke!” she cried, shaking him awake.

“Marie, I don’t think it’s the bed.”

Two weeks before I was due, Mom’s water had broken. An hour later, they were at the local hospital. Their doctor was on vacation, and Mom’s parents were in Utah for cancer treatment.

After twelve hours, Mom was still waiting for her first contractions, so the doctors decided to try to induce the birth. Loaded up on Pitocin, a drug that jump-started a series of painful contractions, Mom went into hard labor around seven that night. Three hours later, I still hadn’t come out, and Dad began to get excited.

“Hold on! A couple more hours and you can have him on your birthday!”

Indeed, the hours inched along, and Mom’s labor continued past the midnight mark. On August 18, I was born. She turned twenty-eight; I turned zero.

I don’t really like this bit. It’s awkward asking my mom what those first few moments of having a legless kid were like. She must have wondered what kind of life her child would have. I can hear the tension in her voice as she tiptoes around the answer.

“Kevin, you were an exclamation point on a really tough couple of years.”

The rest of the phone conversation comes between pauses, white noise between the sighed-out details.

“I could tell from the look on the nurses’ faces that something was wrong. I hadn’t heard you cry. So I started asking, ‘Is he crying? Is everything okay?’ ”

“The doctor looked over at me and said, ‘He doesn’t have any legs.’ I told him, ‘That’s not very funny.’ He said, ‘I’m not joking.’ ”

Silence, as she collects her thoughts.

“The doctors handed you over after that. You were pretty tightly swaddled up in these white hospital blankets. The first thing I did was pull the end of the blanket out so that you looked long enough.

“It was a long process of us becoming comfortable with who you were.”

I don’t think that I would know what to do if I were to become the father of someone with a disability. At the very least, I’d probably be ashamed and disappointed. Knowing that I’d react this way makes me feel guilty for what my parents had to go through.

I’m not as strong as my parents, I think to myself.

Mom pulls me out of the spiral.

“I remember asking if stress could’ve caused … this. The doctor smiled at me. ‘If stress caused it, there’d be babies without legs all over the place.’

“After that, I can’t remember what we asked out loud and what we thought inside.”

It all boiled down to one basic question, though:

What could we have done to have caused this?

My parents felt that there had to be an explanation; something like this couldn’t just happen for no reason. In a way, knowing that a certain drug had been misused, or that there was a problem during my birth, would have been more comforting. At least then, this accident would have a cause.

The doctors sent off the placenta for testing. A panel in another state found the pregnancy to be normal and the placenta to be healthy. Mom didn’t take or do anything she shouldn’t have.

Dad raced home to ring his parents in Connecticut. They originally weren’t going to come out for my birth, But once the information reached them about my lack of legs, Grandma and Grandpa hopped the next flight to Montana.

My dad’s parents met my mom’s at the airport the next day. Already aware of the gravity of the situation, my grandma asked in a solemn tone: “So … how are things?”

My mom’s father laughed. “Everything’s fine as long as you don’t sling him over your shoulder, ’cause there’s nothing to grab.”

While the concern, apprehension, and fear were real, a bit of black humor helped to loosen the knot of tension. Everyone had his or her own crack.

The doctors: “He’ll never be a professional basketball player, but that probably wasn’t going to happen anyway.”

My dad: “Hell of a birthday present.”

Twenty-three years later, even I chime in: “After all that labor? Must’ve been like climbing forty flights of stairs for half a chocolate bar.”

Soon after the tests returned, I was given a label.

“The doctors said it was bilateral amelia. And I asked what that meant,” Mom said.

It basically means “no limbs.” It’s pretty simple. “Treat him like a normal guy, and he’ll have a normal life,” the doctor told her.

Except “normal life” couldn’t really begin yet, since the hospital held me for a week while I was placed under bright lights and tested to see what else could possibly be wrong. To top it off, only my mom and dad were able to hold me — an activity that I’m told grandparents prize highly. Needless to say, the four grandpas and grandmas were getting pretty impatient.

The doctors didn’t budge or give an inkling as to how long they expected to keep me in the hospital. Finally, Dad had had enough. There was a house and a sock drawer retrofitted into a crib with my name on it.

“This s--- isn’t happening anymore,” Dad said. “I’m taking him home.”

“Well, you can’t. The medical proce—”

“I don’t give a damn. I’m taking him home. You can figure out the rest.”

Excerpted with permission from “Double Take” (HarperStudio) by Kevin Connolly.