An in-depth NASA study concludes that while the crew of the Columbia might have been able to be saved had the true state of the shuttle been known in time, the shuttle itself was doomed. In a 34-page presentation, obtained exclusively by MSNBC.com, the NASA team lays out in detail the risks of either repairing Columbia or rescuing the crew with another shuttle.

Throughout the two-week flight of Columbia in January, NASA engineers and managers had wrestled with whether the impact of insulating foam on the shuttle’s wing during launch posed any threat. But neither serious inspection plans nor workable rescue scenarios were ever developed because the need for them wasn’t recognized.

After the Columbia disintegrated, killing its seven-member crew, the independent panel investigating the tragedy asked a NASA team to go back and look at what the space agency might have come up with had that need been recognized. The group, led by experienced flight director John Shannon, was assigned to look at the areas of rescue, repair, entry trajectory redesign, and combinations of these three.

The NASA team described their findings in an oral presentation on May 22 to the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, which verbally described the findings to the news media. But both NASA and CAIB declined to to provide the briefing documents on which those findings were based; documents that MSNBC.com has since obtained.

Parallel tracks: Rescue, repair

The study rests on two major assumptions:

- That there was a recognized catastrophic threat to the shuttle and crew, either from a 6-inch hole in the leading edge of the wing, or a 10-inch gash from the loss of a panel-to-panel seal.

- That NASA management was willing to risk another shuttle launch even before the cause of the fatal damage to the first was known.

From those assumptions, the NASA team developed a timeline of events:

On the third day of flight, military photography of the damaged wing would be taken, while the crew and engineers on the ground planned for an inspection spacewalk, if needed. That spacewalk would take place on the fifth flight day, at which point the lethality of the damage would be known for certain and the emergency procedures initiated.

For the next twenty days, work would proceed in parallel on two options: rescue and repair.

The rescue option depended on whether the shuttle Atlantis could be prepared for launch in such a short time. If it became clear that Atlantis was not going to be ready in time, Columbia’s crew would expend their remaining supplies in the two additional spacewalks needed to make a jury-rigged fix to the hole, and then trust their lives to the repairs and try to land on their own.

Inspection spacewalk

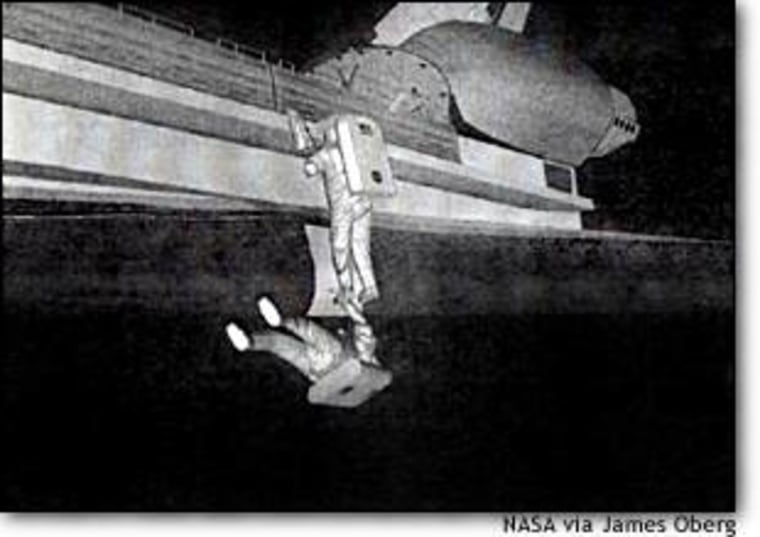

The inspection spacewalk itself would have been almost trivial, the NASA team discovered, requiring neither a risky free-flight by an untethered astronaut nor complicated lash-up ladders. The two trained spacewalkers aboard Columbia, Mike Anderson and David Brown, would have been able to do it with their hands.

Since the shuttle’s bay doors folded open and down over the wings, the outer edge of a door was already only four feet above the wing surface. One astronaut would grab the door edge with his hands and extend his lower body down to the top of the wing, his feet cushioned by towels to prevent tile damage. The other crewman would then climb down the first astronaut’s body and peek over the wing’s leading edge at the damaged thermal shield. Eyeball descriptions, and photographs, would document the severity of the damage.

As to the problem of extending the Columbia mission until a rescue shuttle arrived, space doctors struggled with how to extend the existing 68 cans of lithium hydroxide — a chemical which absorbs carbon dioxide from the air — from the planned 20 days (this included contingency extension days) to a full 30 days. If the crew could be kept asleep for 12 hours per day — perhaps with medication — the 30 days would have been achievable without ever going over the 2 percent carbon dioxide concentration that is the standard maximum allowable level. But even in a situation where the crew slept only eight hours a day, 30 days was reachable if the carbon dioxide concentration was allowed to reach 3.5 percent, a level the doctors considered “acceptable.”

Columbia already contained enough of every other category of “consumable,” including oxygen, which was used both for breathing and power. The plan would be to allow one inspection spacewalk, then power the shuttle down to below 10 kilowatts — about a third of the level of full operation — and wait out the rescue launch.

Repairing Columbia

The repair plans described in the NASA documents are highly innovative. The engineers examined all materials inside and outside the shuttle and its Spacehab science module, and compiled a long list of candidates.

If there was a hole in one of the panels, the preferred solution was to use “sacrificial materials to temporarily block the plasma flow” into the hole. A bag filled with scrap metal would go in first, followed by some spare collapsible water containers. The containers would then be filled with a line running from the airlock water supply valve, and left to freeze. Additional water would be freely sprayed into remaining gaps, to flash freeze, and the hole would be covered with insulation blankets torn off the top of the payload bay door. A Teflon cover would be taped in place to hold it all in until re-entry.

The solution to a crack between neighboring panels was even more ingenious. Once the gap had been measured on the first spacewalk, a second spacewalk would scavenge tile from the “canopy area” around the front windows. The tile would be brought back inside, sculpted with medical knives, and pressed into fit the gap on another spacewalk.

In either case, the first of two repair spacewalks would also be used to move a ladder from the cabin’s middeck onto the edge of the bay door, leading to the work area. Additional time outside could be used to jettison heavy equipment to “lighten the ship.”

The analysis team rated repairing the shuttle as having a “high” level of difficulty, with the risk of additional damage to the shuttle also “high.” The risk to the crew, however, was rated as “moderate” and since the shuttle was presumably already fatally wounded, add-on hazards hardly mattered.

Lightening the space shuttle and descending with a “low-drag profile” or a high angle of attack were also considered by the NASA team. Benefits were seen, but at the cost of shifting the heat load elsewhere: “None of these options will be successful independently,” the report concluded, “but added together they may make a difference.”

Since the repairs could not be guaranteed to work, the team did not want to risk the astronauts’ lives with a wing collapse near the runway and instead proposed that the shuttle crew wait until Columbia had reached an altitude of 35,000 feet and then parachute out.

“Team consensus that bailout will be performed,” the report stated, “due to uncertainties in wing and landing gear structure.”

After the crew had jumped, the Columbia would steer by autopilot to crash over an uninhabited area.

The rescue option

If the ground processing at Cape Canaveral was fast enough, this risky repair option might have been avoidable. Atlantis could have used a standardized rendezvous profile. Columbia’s crew would have positioned the shuttle top down in orbit, with its left wing leading. Atlantis would have moved up directly below it, its nose leading, with its open payload bay pointed directly towards the open bay of Columbia.

Two spacewalkers from Atlantis would deploy a pole from their spaceship to the other, and cross hand-over-hand to Columbia. They would retrieve two Columbia astronauts in that ship’s only two spacesuits. They would also leave behind them two new spacesuits in the Columbia airlock and some air purifying chemicals to get the carbon dioxide under control.

This process would repeat three more times to retrieve the full crew. The transfer would take several hours, as the two shuttles flew in tandem.

Once the rescued astronauts were aboard Atlantis, Columbia would be remote-controlled to a destructive atmospheric entry over the ocean.

For the return to Earth, the seven rescued astronauts would lie on their backs on the floor of the lower deck of Atlantis and strap themselves in.

In every option, then, the shuttle Columbia was doomed. But enough realistic options to save the crew had turned up, and a bigger team with more urgency could well have found even more. The tragedy was that this time the curtain never went up on NASA’s space miracle workers.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at the Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer.