The foam impact test on Monday that left a gaping hole in a simulated space shuttle wing also graphically unveiled the gaping hole in NASA’s safety culture. Even without any test data to support them, NASA’s best engineers who were examining potential damage from the foam impact during Columbia’s launch made convenient assumptions. Nobody in the NASA management chain ever asked any tough questions about the justification for these feel-good fantasies.

The shocking flaw was just another incarnation of the most dangerous of safety delusions — that in the absence of contrary indicators, it is permissible to assume that a critical system is safe, even if it hasn’t been proved so by rigorous testing. The absence of evidence for the absence of safety, so this delusion goes, is adequate proof of the presence of safety.

In the past, the shuttle Challenger was lost in 1986, and four Mars probes vanished in 1999, and Hubble’s mirror was ground wrong, for exactly this reason. And again, this new test tells us, the NASA culture forgot how dangerous this delusion could be.

Experts with the Columbia Accident Investigation Board have kept the news media fully informed of their activities and thinking during the five-month investigation. In both on-the-record and off-the-record “for background” meetings, they have provided in-depth discussions of all issues under consideration.

For example, board members carefully explained why the impacts of foam — the so-called Spray-On Foam Insulation, or SOFI, attached to the shuttle propellant tank to prevent the formation of dangerous sheets of ice — on tiles were very different than the impacts of the same material on reinforced carbon-carbon, or RCC, the super-heat-resistant sheets that line the leading edge of shuttle wings.

“Tiles are supported under their entire area by their contact with the aluminum wing surface,” reporters were told. “But each RCC panel is only supported by bolts at its corners.” This leaves empty space behind the third-of-an-inch material, that could allow deflection if struck by a powerful blow.

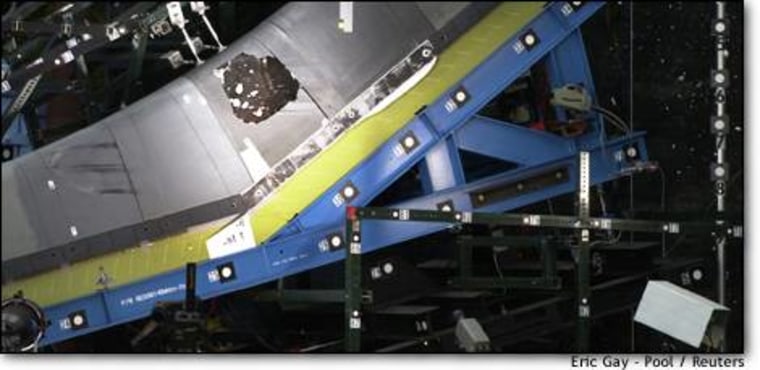

And even testing against one panel would have had inadequate fidelity, the CAIB investigators found. A month ago, using fiberglass panels to stand in for more expensive and rare flight-qualified RCC panels, the tests surprised everyone by showing how an impact would distort the relative positions of different pieces of the wing, leading to unexpected stresses and gaps. Before the test, nobody had predicted this — so NASA seems to have assumed it wouldn’t happen.

Early in the current series of air-gun impact tests conducted at a NASA contractor laboratory in San Antonio, one of the board’s members was asked if they had as yet found any record that NASA had ever tested — or ever thought there was a need to test — foam impact on the RCC panels. He had found none. On two occasions, RCC panels were shot with high-speed pellets to simulate micrometeorite impact — but foam impact was never simulated.

Yet when Boeing engineers responsible for operating the shuttle fleet reported their findings to NASA during the Columbia’s flight, they explicitly ruled out any concern from SOFI hitting RCC, even though they admitted that “flight condition is significantly outside the test database.”

Despite this, they told NASA’s mission management team that the RCC could “withstand impacts of at least 15 degrees,” and they assumed “a much greater capability” based on an obvious factor: “relative softness of SOFI.” They concluded that “RCC damage [is] limited to [loss of] coating based on soft SOFI,” and as one test case they had actually studied impact on RCC panel No. 9’s lower flange area — only inches away from the actual impact location.

The predicted results: “Assume coating loss and carbon substrate exposed.” The thermal damage from such a postulated consequence was some slight erosion that was considered, simply, “No Issue.”

The analysis used different foam weights ranging up to 2.5 pounds (1.1 kilograms), almost twice as heavy as the actual impact fragment. Impact speeds and angles were properly estimated, and potential damage to tiles was predicted correctly, as confirmed in later testing.

But there was a hole in the logic big enough for Death to enter. There was no test data to support the happy assumptions of armorlike RCC panel invulnerability. Nobody who reviewed the study’s results, all the way to the top, noticed this.

Nor could the CAIB investigators find any evidence that for all the safety teams and hazard analyses, anyone had asked for proof that the RCC could withstand a fairly typical foam fragment hitting it during launch. Instead, in the absence of evidence that it could not — evidence that showed up Monday, but that NASA had never before sought — the convenient assumption of “it must be safe” carried the day.

The Columbia astronauts were never given the chance to try to fill the hole in their wing with repair materials and make a desperate plunge back to Earth. Now NASA is confronted with unavoidable proof of an even more appalling hole in its safety culture. Until it finds reliable, perpetual ways to patch that gap in the minds of every space worker, the avoidable hazards that have cost so much in lives, treasure and time will still threaten new disasters.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at the Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer.