The Antarctic ice sheet holds enough frozen water to be a major player in the climate change game if it melts. Concerned about a range of possibilities, from rising sea level to upsets in the oceans’ circulation patterns, scientists have been scrutinizing the continent for signs of change. A new report in the journal Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, suggests that the ice sheet’s edges are most vulnerable to climate warming, and are melting faster than scientists had realized.

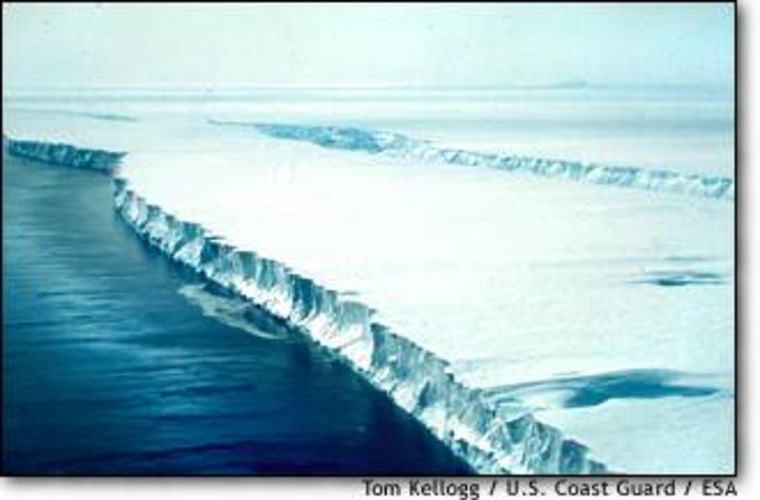

Like the brim of a hat upon someone’s head, the edges of the Antarctic ice sheets extend past their “grounding lines,” the boundary where they attach to the land below. From there, they float out into the ocean, forming great shelves of ice. The seawater that bathes the shelves’ underbellies can be several degrees above freezing — hardly a balmy temperature, but still warm enough to do the trick.

Eric Rignot of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Stanley Jacobs of Columbia University surveyed 23 glaciers that flow off the Antarctic ice sheet. On average. the ice near the grounding lines was melting away twice as fast as the rate scientists had previously predicted for the ice shelves overall.

Because the ice shelves are already floating, melting at their bases alone wouldn’t cause sea level to rise. But it may lead to important changes on the rest of the ice sheet, Jacobs said, such as faster-flowing glaciers or a possible “crack-up” of parts of the ice sheet.

The yearly thinning at the ice shelf bases ranged from 4 meters (13 feet), for some glaciers, to 40 (130 feet), in the case of the Pine Island Glacier, the researchers found.

“It was a little surprising to us, because there had not been reports in the literature of melting rates quite this high,” Jacobs said.

Vulnerability to ocean warming

The researchers don’t know at this point whether these melting rates have increased over time. But, they can make some estimates about the future, in which it’s generally thought that ocean temperatures will increase, due to greenhouse warming from fossil fuel burning.

“To the extent that the ocean warms, and that warm water reaches beneath the ice shelf, it’s very likely to increase the rate of melting near the grounding line in particular. That could have a number of effects,” Jacobs said.

From their observations, the researchers estimate that for each rise in ocean temperature of 0.1 degree Celsius (0.2 degree Fahrenheit), the melting rate near the grounding line should increase by 1 meter (39.37 inches) per year.

Scientists have already detected a 0.2 degree C (0.36 degree F) increase in recent decades. This rise is large enough to explain the rapid thinning observed for ice shelves in some parts of Antarctica, and the acceleration of the glaciers that nourish them, according to the researchers.

Water temperature isn’t the only culprit behind the melting Rignot and Jacobs studied. The grounding lines of some ice shelves are so deep that water there is under quite a bit more pressure than at the surface. Even if that water is freezing or below, it can still melt the ice at depth, the researchers said.

Beyond the fringes

Melting at the base of the ice shelves could have implications for the rest of the ice sheet. The 23 shelves in the Science study collectively drain more than one third of the area of continental Antarctica, funneling the ice via a network of ice streams through narrow exit gates.

Some scientists believe that the shelves may be buttressing the glaciers like bookends, and that without their support, the ice streams might slither more rapidly into the ocean.

There may also be a connection between melting at the edges and the ice sheet’s overall stability.

“One of the interesting things about the sea floor in that area, is it tends to get deeper as you move inward, because the ice is heavy and depressing continent,” Jacobs said.

In these areas, the grounding line might recede so far that seawater would undercut a lot more of the ice sheet than it does now, according to the researchers. With their foundation eroded, large chunks of the ice sheet could collapse into the ocean, scientists have proposed.

Surveying from space

To determine the melting rates at the grounding lines, Rignot and Jacobs used a technique called laser interferometry, which shoots a laser beam down from a satellite, and analyzes the speed, direction, and other changes in the beam that bounces back. From this information, the researchers could distinguish between ice that moved with the tides and ice resting on solid ground, and thus pin down the exact locations of the grounding lines.

They also measured how much ice was moving across the grounding line, and compared it to the measurement of ice moving past another point near the front of the shelf. From the difference, and the area of the shelf between the two points, the researchers were able to calculate how much ice must be disappearing.

The fate of the Antarctic ice sheet has been a matter of debate for some time, with a major focus on how ice is moving on the continent. The Science study now reveals a new aspect of the Antarctic ice sheet to consider: its floating margins, ever-subject to the waters on which they rest.