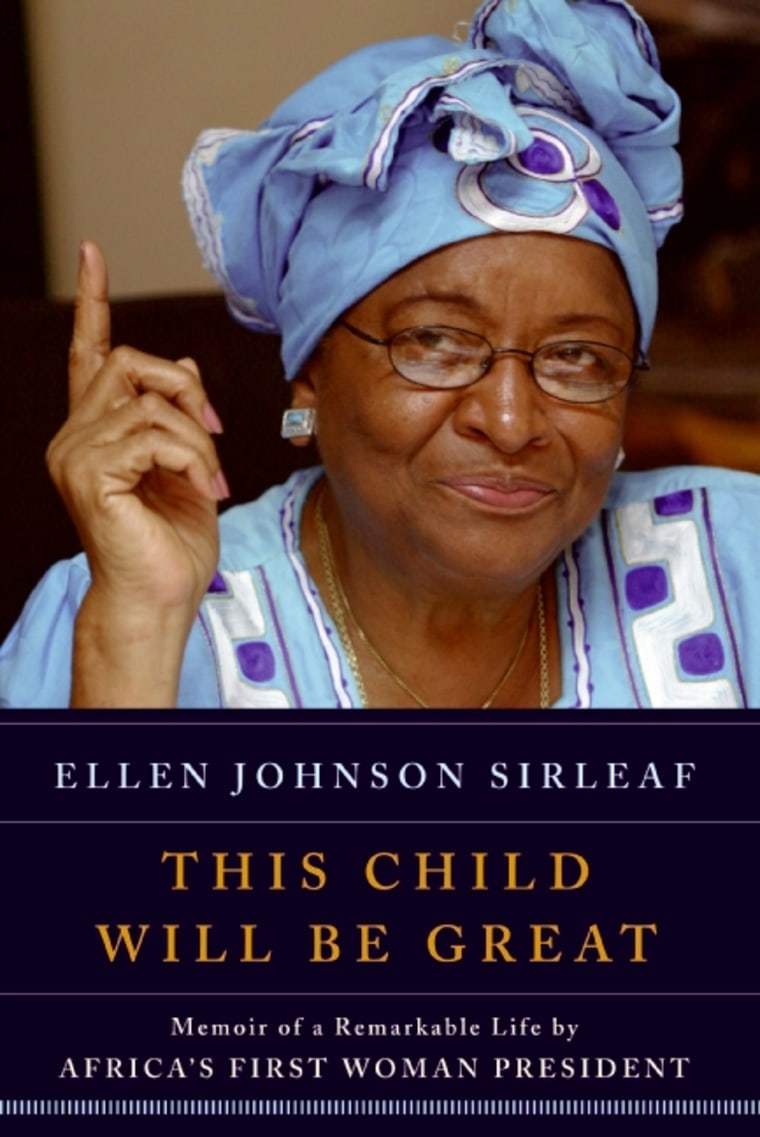

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the 23rd elected president of Liberia, is Africa's first female elected president. In her political and personal memoir, “This Child Will Be Great,” Sirleaf shows her determination and courage through stories about her happy childhood and unhappy marriage, and gives an inside look at a country that is working to rebuild itself.

Prologue

If asked to describe my homeland in a sentence, I might say something like this: Liberia is a wonderful, beautiful, mixed-up country struggling mightily to find itself.

Given more space, however, I would certainly elaborate.

Liberia is some 43,000 square miles of lush, well-watered land on the bulge of West Africa, a country slightly larger than the state of Ohio, a lilliputian nation with a giant history. It has a population of 3.5 million people from some sixteen ethnic groups speaking some sixteen indigenous languages plus English. It has never known hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, droughts, or other natural disasters, only the occasional flood and the more frequent havoc wreaked by man. Liberia is complicated. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, Liberia is a conundrum wrapped in complexity and stuffed inside a paradox. Then again, it was born that way.

The first inhabitants of the region now known as Liberia may have been Jinna, or pygmies, according to the Liberian historian Abayomi Karnga. Soon came the Gola, whom many historians believe to be the first traveling settlers of the land. Gola legend has it that the tribe left Central Africa and moved toward the coast in search of land. Ruthless fighters, they went through and not around the tribes in their path, according to the book “Notes from the New Liberia: A Historical and Political Survey.” The Gola and the Kissi belong to the Mel (West Atlantic) ethnolinguistic group.

The Mande linguistic group, made up of the Mandingo, the Vai (one of only a few African tribes to have developed a script), the Gbandi, the Kpelle, the Loma (who also had a script), the Mende, the Gio, and the Mano peoples, is believed to have entered the area from the northern savannas in the fifteenth century. The third major group, the Kwa linguistic group, includes the Bassa, Dei (Dey), Grebo, Kru, Belle (Kuwaa), Krahn, and Gbee peoples, found mostly in the southern and eastern parts of Liberia.

All of these groups were living in the land when the final group of settlers began to arrive. These were the Americo-Liberians.

As early as the 1700s, the idea of sending New World slaves “back” to Africa rose in the hearts and minds of British abolitionists, who saw, in the establishment of a colony for former slaves, a means of ending the slave trade — and, eventually, slavery itself.

During the American Revolutionary War, African slaves in the American colonies were promised freedom if they sided with the British. Many did, fighting valiantly. When the war ended, several hundred of these fighters gathered their families and fled the country with the departing British troops. After some wandering, they were settled, with British backing, along the coast of West Africa in what is now the country of Sierra Leone. Although most of those first, early settlers perished of malaria and yellow fever, subsequent attempts at settlement took firmer hold. The first of these was established in 1792. The settlers called their new city Freetown.

Meanwhile, a similar conversation was taking place across the pond in the newly born United States of America. Paul Cuffee was the freeborn son of a former slave father and a Native American mother. A prominent Quaker, Cuffee became a sailor and successful shipowner who opened the first integrated school in Massachusetts and later began advocating to settle freed slaves in Africa. In 1816, at his own expense but with the backing of the British government and some members of the U.S. Congress, Captain Cuffee took thirty-eight American blacks to Freetown and settled them there. He intended to make this voyage an annual affair, but his untimely death in 1817 put an end to the plans.

Still, Cuffee had reached a large audience with his procolonization arguments. Not all supporters of the idea, however, had arrived at their destination from the same starting point.

Some abolitionists took up the cry as part of their attack on slavery, while some religious adherents thought the idea an excellent means of spreading Christianity to “the dark continent.” Some white Americans, considering themselves pragmatists, thought black people would simply be happier and fare better in Africa, where they could live free of the racial discrimination that gripped America. Others simply wanted to rid the new country of all black people as soon as possible.

In this last group stood the statesman Thomas Jefferson. Writing in his 1781 Notes from the State of Virginia, Jefferson advocated gradually emancipating all slaves and shipping them to Africa, along with free blacks and possibly those of mixed heritage. Jefferson — an author of the American Declaration of Independence and its famous, stirring words “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” — was, of course, a slave owner himself. He considered black people inferior to whites and warned that their continuing presence was a threat to the young nation he had helped to found. They could not simply be freed and allowed to remain in the United States, Jefferson warned. They had to go.

“Among the Romans emancipation required but one effort,” he wrote. “The slave, when made free, might mix with, without staining the blood of his master. But with us a second is necessary, unknown to history. When freed, he is to be removed beyond the reach of mixture.”

This, then, was the backdrop against which the American Colonization Society was founded in 1816 in Washington, D.C. Among the founders were many prominent early American leaders, including Daniel Webster, Francis Scott Key, Henry Clay, and Bushrod Washington, an associate justice of the Supreme Court and the nephew of George Washington himself (and after whom Bushrod Island in Monrovia is named).

The society began raising funds to establish a colony in Africa. Four years later, in January of 1820, the ship Elizabethset sail from New York. On board were eighty-six free American blacks from New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and Virginia — more than half of them women and children — along with three agents of the ACS. It took six weeks to cross the Atlantic, and the eager immigrants landed first on Sherbo Island off the coast of present-day Sierra Leone, intending to use the spot as a stopping ground while they searched for permanent accommodations on the nearby mainland.

But disease and fever laid waste to much of the group; by May 1820, all three agents and nearly a quarter of the would-be settlers were dead. Those who survived fled to Freetown to recover and repair.

A year later the society sent a new agent, Dr. Eli Ayres, to explore the coast and negotiate with local Dey and Bassa chiefs for suitable land for a settlement. Under the direction of President James Monroe, Dr. Ayres enlisted the help of Lieutenant Robert Stockton, captain of the USS Alligator, a naval ship patrolling the West African coastline in cooperation with His Majesty’s Navy’s slave-trading blockade. Together Ayres and Stockton settled their sights on a slip of land two hundred or so miles south of Freetown known as Cape Montserado, or Mesurado. Agents of the ACS had previously tried to buy this very land, but the local Bassa chief, King Peter, had declined to sell.

This time, however, Stockton declined to take no for an answer. When King Peter again seemed reluctant to sell, Stockton persuaded him with a pistol to the head. Thus, in December 1821, the ACS gained a toehold in Africa in exchange for some $300 worth of goods, including muskets, gunpowder, nails, beads, tobacco, shoes, soap, and rum. Stockton also promised that the new immigrants would not interfere with the thriving local slave trade.

Soon afterward, the surviving settlers from the Elizabeth, replenished by a fresh ship full of immigrants, took possession of the land. They gave thanks, dubbing their new home Providence Island, and then moved immediately to secure the adjacent mainland. There the first permanent settlement, originally called Christopolis, was carved from the thick forest. In 1824, the settlement’s name was changed to Monrovia, in honor of U.S. President (and ACS member) James Monroe, and the colony as a whole became the Commonwealth of Liberia.

But the colony, being neither a sovereign nation nor a bona fide colony of a sovereign government (the United States refused to formally designate it as such) faced ever-increasing political threats from foreign governments, especially Britain. So on July 26, 1847, the country declared independence in a document that referenced the oppression of African Americans in the United States and stated that such persons were being driven to make new lives for themselves in Africa.

And so Liberia was born.

Britain was one of the first governments to recognize the new nation; the United States did not recognize Liberia until the American Civil War.

Nonetheless, that initial settler group, and those who followed, came to call themselves Americo-Liberians. It was an appropriate name, for this band of hopeful immigrants was far more American than African and intended to remain that way. They had adopted the cultures, traditions, and habits of the land of their birth, and these they brought with them when they came.

The colonists spoke English and retained the dress, manners, housing, and religion of the American South. They created symbols for this new nation that reflected, to a sometimes startling degree, their American identity and emigrant sensibility. The Liberian flag mimics so closely the American flag that it is easy to mistake it for the latter; the only difference is the number of stars and stripes. The Liberian seal features not only a palm tree, representing our vast natural resources, but a sailing ship to represent the settlers who came from across the seas.

The Liberian motto is “The love of liberty brought us here.” Several passages of our original Declaration of Independence might sound familiar to American ears: “We the People of the Commonwealth of Liberia, in Africa, acknowledging with devout gratitude, the goodness of God ... do, in order to secure these blessings for ourselves and our posterity, and to establish justice, insure domestic peace, and promote the general welfare, hereby solemnly associate, and constitute ourselves a Free, Sovereign and Independent State, by the name of the REPUBLIC of LIBERIA, and do ordain and establish this Constitution for the government of the same.”

The settlers of modern-day Liberia decided they would plant their feet in Africa but keep their faces turned squarely toward the United States. This stance would trigger a profound alienation between themselves and the indigenous peoples upon whose shores they had arrived and among whom they would build their new home. Alienation would lead to disunity; disunity would lead to a deeply cleaved society.

That cleavage would set the stage for all the terror and bloodshed to come.

Excerpted with permission from “This Child Will Be Great” by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (Harper).