When Susan Axelrod tells the story of her daughter, she begins like most parents of children with epilepsy: The baby was adorable, healthy, perfect. Lauren arrived in June 1981, a treasured first-born. Susan Landau had married David Axelrod in 1979, and they lived in Chicago, where Susan pursued an MBA at the University of Chicago and David worked as a political reporter for the Chicago Tribune. (He later would become chief strategist for Barack Obama's Presidential campaign and now is a senior White House adviser.) They were busy and happy. Susan attended classes while her mother babysat. Then, when Lauren was 7 months old, their lives changed overnight.

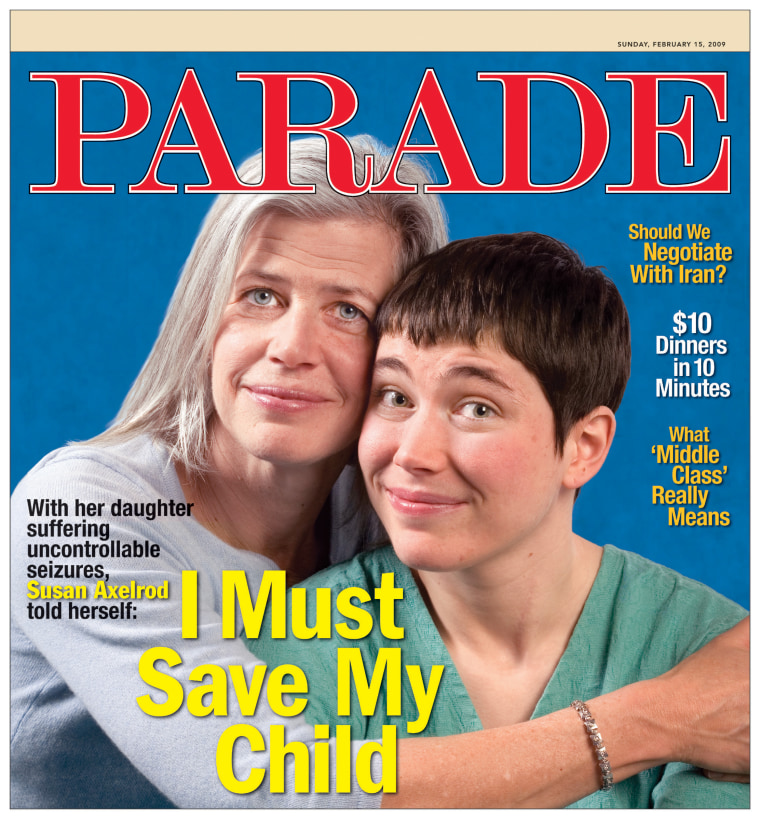

“She had a cold,” Susan tells me as we huddle in the warmth of a coffee shop in Washington, D.C., on a day of sleet and rain. Susan is 55, fine-boned, lovely, and fit. She has light-blue eyes, a runner's tan, and a casual fall of silver and ash-blond hair. When her voice trembles or tears threaten, she lifts her chin and pushes on.

“The baby was so congested, it was impossible for her to sleep. Our pediatrician said to give her one-quarter of an adult dose of a cold medication, and it knocked her out immediately. I didn't hear from Lauren the rest of the night. In the morning, I found her gray and limp in her crib. I thought she was dead.

“In shock, I picked her up, and she went into a seizure — arms extended, eyes rolling back in her head. I realized she'd most likely been having seizures all night long. I phoned my mother and cried, 'This is normal, right? Babies do this?' She said, 'No, they don't.'”

The Axelrods raced Lauren to the hospital. They stayed for a month, entering a parallel universe of sleeplessness and despair under fluorescent lights. No medicine relieved the baby. She interacted with her parents one moment, bright-eyed and friendly, only to be grabbed away from them the next, shaken by inner storms, starting and stiffening, hands clenched and eyes rolling. Unable to stop Lauren's seizures, doctors sent the family home.

The Axelrods didn't know anything about epilepsy. They didn't know that seizures were the body's manifestation of abnormal electrical activity in the brain or that the excessive neuronal activity could cause brain damage. They didn't know that two-thirds of those diagnosed with epilepsy had seizures defined as “idiopathic,” of unexplained origin, as would be the case with Lauren. They didn't know that a person could, on rare occasions, die from a seizure. They didn't know that, for about half of sufferers, no drugs could halt the seizures or that, if they did, the side effects were often brutal. This mysterious disorder attacked 50 million people worldwide yet attracted little public attention or research funding. No one spoke to the Axelrods of the remotest chance of a cure.

At home, life shakily returned to a new normal, interrupted by Lauren's convulsions and hospitalizations. Exhausted, Susan fought on toward her MBA; David became a political consultant. Money was tight and medical bills stacked up, but the Axelrods had hope. Wouldn't the doctors find the right drugs or procedures? “We thought maybe it was a passing thing,” David says. “We didn't realize that this would define her whole life, that she would have thousands of these afterward, that they would eat away at her brain.”

“I had a class one night, I was late, there was an important test,” Susan recalls. “I'd been sitting by Lauren at the hospital. When she fell asleep, I left to run to class. I got as far as the double doors into the parking lot when it hit me: 'What are you doing?'” She returned to her baby's bedside. From then on, though she would continue to build her family (the Axelrods also have two sons) and support her husband's career, Susan's chief role in life would be to keep Lauren alive and functioning.

The little girl was at risk of falling, of drowning in the bathtub, of dying of a seizure. Despite dozens of drug trials, special diets, and experimental therapies, Lauren suffered as many as 25 seizures a day. In between each, she would cry, “Mommy, make it stop!”

While some of Lauren's cognitive skills were nearly on target, she lagged in abstract thinking and interpersonal skills. Her childhood was nearly friendless. The drugs Lauren took made her by turns hyperactive, listless, irritable, dazed, even physically aggressive. “We hardly knew who she was,” Susan says. When she acted out in public, the family felt the judgment of onlookers. "Sometimes," Susan says, “I wished I could put a sign on her back that said: 'Epilepsy. Heavily Medicated.'”

At 17, Lauren underwent what her mother describes as “a horrific surgical procedure.” Holes were drilled in her skull, electrodes implanted, and seizures provoked in an attempt to isolate their location in the brain. It was a failure. “We brought home a 17-year-old girl who had been shaved and scalped, drilled, put on steroids, and given two black eyes,” Susan says quietly. “We put her through hell without result. I wept for 24 hours.”

The failure of surgery proved another turning point for Susan. “Finally, I thought, 'Well, I can cry forever, or I can try to make a change.' ”

Susan began to meet other parents living through similar hells. They agreed that no federal agency or private foundation was acting with the sense of urgency they felt, leaving 3 million American families to suffer in near-silence. In 1998, Susan and a few other mothers founded a nonprofit organization to increase public awareness of the realities of epilepsy and to raise money for research. They named it after the one thing no one offered them: CURE — Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy.

“Epilepsy is not benign and far too often is not treatable,” Susan says. “We wanted the public to be aware of the death and destruction. We wanted the brightest minds to engage with the search for a cure.”

Then-First Lady Hillary Clinton signed on to help; so did other politicians and celebrities. Later, veterans back from Iraq with seizures caused by traumatic brain injuries demanded answers, too. In its first decade, CURE raised $9 million, funded about 75 research projects, and inspired a change in the scientific dialogue about epilepsy.

“CURE evolved from a small group of concerned parents into a major force in our research and clinical communities,” says Dr. Frances E. Jensen, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. “It becomes more and more evident that it won't be just the doctors, researchers, and scientists pushing the field forward. There's an active role for parents and patients. They tell us when the drugs aren't working.”

The future holds promise for unlocking the mysteries of what some experts now call Epilepsy Spectrum Disorder. “Basic neuroscience, electrophysiological studies, gene studies, and new brain-imaging technologies are generating a huge body of knowledge,” Dr. Jensen says.

Lauren Axelrod, now 27, is cute and petite, with short black hair and her mother's pale eyes. She speaks slowly, with evident impairment but a strong Chicago accent. “Things would be better for me if I wouldn't have seizures,” she says. “They make me have problems with reading and math. They make me hard with everything.”

By 2000, the savagery and relentlessness of Lauren's seizures seemed unstoppable. “I thought we were about to lose her,” Susan says. “Her doctor said, 'I don't know what else we can do.'" Then, through CURE, Susan learned of a new anti-convulsant drug called Keppra and obtained a sample. “The first day we started Lauren on the medication,” Susan says, “her seizures subsided. It's been almost nine years, and she hasn't had a seizure since. This drug won't work for everyone, but it has been a magic bullet for Lauren. She is blooming.”

Susan and David see their daughter regaining some lost ground: social intuition, emotional responses, humor. “It's like little areas of her brain are waking up,” Susan says. “She never has a harsh word for anyone, though she did think the Presidential campaign went on a little too long. The Thanksgiving before last, she asked David, 'When is this running-for-President thing going to be finished?' ”

CURE is run by parents. Susan has worked for more than a decade without pay, pushing back at the monster robbing Lauren of a normal life. “Nothing can match the anguish of the mom of a chronically ill child,” David says, “but Susan turned that anguish into action. She's devoted her life to saving other kids and families from the pain Lauren and our family have known. What she's done is amazing.”

“Complete freedom from seizures — without side effects — is what we want,” Susan says. “It's too late for us, so we committed ourselves to the hope that we can protect future generations from having their lives defined and devastated by this disorder.”

For more stories about families and the health challenges their children face, visit Parade.com.