Rhesus macaque monkeys performed nearly as well as college students at quick mental addition, researchers reported Monday, adding to the evidence that non-verbal math skills are not unique to humans.

The study from Duke University follows findings by Japanese researchers earlier this month that young chimpanzees performed better than human adults at a memory game.

Prior studies have found that non-human primates can match numbers of objects, compare numbers and choose the larger number of two sets of objects.

"This is the first study that looked at whether or not they could make explicit decisions that were based on mathematical types of calculations," said Jessica Cantlon, a cognitive neuroscience researcher at Duke whose work appeared in the open-access journal PLoS Biology.

"It shows when you take language away from a human, they end up looking just like monkeys in terms of their performance," Cantlon told Reuters in a telephone interview.

Her study pitted Boxer and Feinstein — two female rhesus macaques named after U.S. Sens. Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein of California — against 14 Duke University students.

"We had them do math on the fly," Cantlon said.

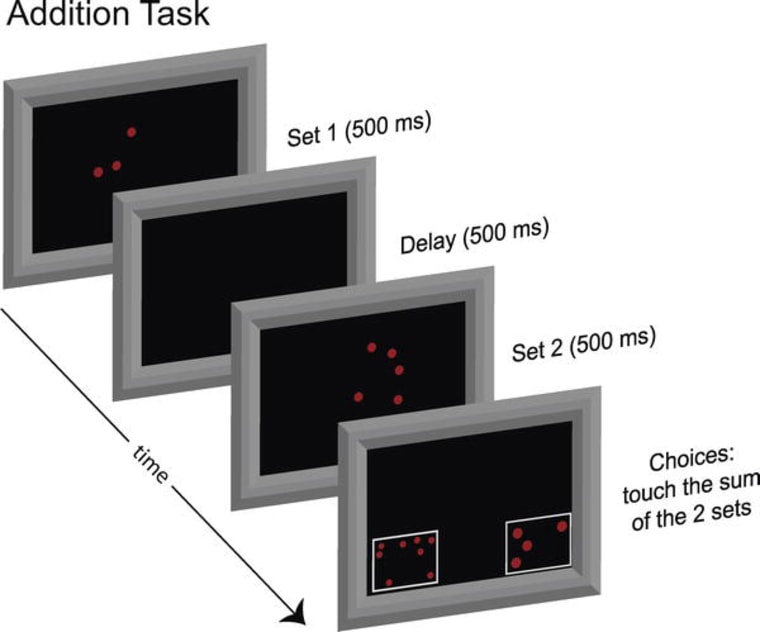

The task was to perform mental addition on two sets of dots that were briefly flashed on a computer screen. The teams were asked to pick the correct answer from two choices on a different screen.

The humans were not allowed to count or verbalize as they worked, and they were told to answer as quickly as possible. The monkeys and the humans all typically answered within 1 second.

The college students answered correctly 94 percent of the time, while the monkeys were right 76 percent of the time. Both the monkeys' and the students' performance worsened when the two choice boxes were close in number, following a similar downward-sloping curve.

"If the correct sum was 11 and the box with the incorrect number held 12 dots, both monkeys and the college students took longer to answer and had more errors," Cantlon explained in a Duke news release. "We call this the ratio effect. What's remarkable is that both species suffered from the ratio effect at virtually the same rate."

Cantlon told Reuters that the study was not designed to show up Duke University students. "I think of this more as using non-human primates as a tool for discovering where the sophisticated human mind comes from," she said.

The researchers said the findings shed light on the shared mathematical abilities in humans and non-human primates and shows the importance of language — which allows for counting and more advanced calculations — in the evolution of math in humans.

"I don't think language is the only thing that differentiates humans from non-human primates, but in terms of math tasks, it is probably the big one," she said.

As for the teams, both were paid. Boxer and Feinstein got their favorite reward: a sip of Kool-Aid soft drink. As for the students, they got $10 each — enough for a beer or two.

This report includes information from Reuters and msnbc.com.