Want to really impress your date this Valentine’s Day? Give that celebratory glass of wine a swirl and a sniff and show off your knowledge. What’s that you detect? A hint of oak? A soupçon of citrus? Just a flutter of volatile terpenoid?

OK, so maybe scientists don’t use the most romantic language, but that doesn’t mean they can’t appreciate a peppery Petite Syrah or a buttery Chardonnay. It’s just that their discerning technological palates delve a little deeper, searching for the specific chemical compounds that make a wine fine. Learning more about these tiny but potent packets of flavor and aroma could help winemakers fine-tune their product with a mixture of vineyard science and art, according to a pair of University of British Columbia researchers.

The mix of volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, in a finished wine is partly responsible for “whether you find the bouquet and entry from a newly opened bottle to be a pleasant experience or the basis for a scowl and a wrinkle of the nose,” Steven Lund and Joerg Bohlmann write in Friday’s issue of the journal Science, published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

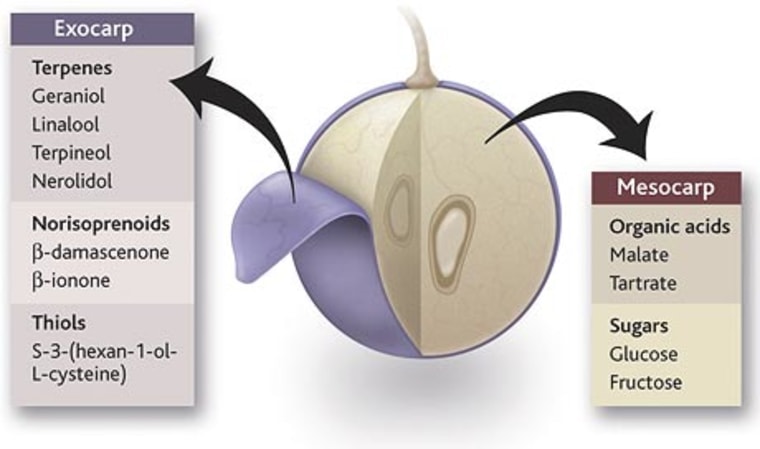

VOCs are the chemicals behind the distinctive tastes and smells we associate with plant foods, including wine grapes. Different VOCs are produced at different times in a plant’s growth, flowering and fruit development. In wine grapes, for instance, VOCs tend to accumulate after the grape seed matures and as the flesh and the skin of the fruit ripen. The balance of tart acids and sugars in the fruit also changes over time.

Unlike citrus fruits or peppermint plants, which have special glands in their peels and leaves that store VOCs, wine grapes trap VOCs by bonding them to other molecules such as sugars and amino acids. Winemakers release VOCs by physically breaking these bonds (a little grape stomping, anyone?) and chemically breaking them during fermentation with grape and yeast enzymes.

Wine grapes usually contain a variety of VOCs, although one particular VOC may dominate as the wine’s finished flavor or “character,” according to Lund and Bohlmann. The “grassy” taste of Sauvignon Blanc comes primarily from compounds called methoxypyrazines, while the terpenoid compounds geraniol and citronellol give the sweet sparkling Muscat wines a floral or fruity character.

Humans can detect very tiny amounts of these compounds, sometimes responding to a flavor that is present at the level of parts per trillion. This keen appreciation may have its roots in ancestral eating habits, the researchers say. For instance, methoxpyrazines are produced in green or unripe plant tissue and gradually disappear as the plant matures. Foragers may have developed a special sensitivity to the compounds as a way of avoiding unripe and less nutritious fruit, a sensitivity that came in handy much later for appreciating the green flavor of a Sauvignon Blanc.

A high-tech pour

Researchers and winemakers have long studied how differences in land, climate, vine varieties and techniques like pruning and watering change the character of wine grapes and finished wines, sometimes from year to year. One of science’s challenges is to show how all these variables affect the complex molecular processes that produce VOCs in wine grapes, Lund and Bohlmann write.

Research in this area “is very much in its infancy,” Lund said, although some scientists have taken the first steps by identifying some of the genes and analyzing the enzymes that produce VOCs in grapevines. Research teams are also beginning to use high-tech detection tools such as mass spectrometry, a precise instrument that calculates the mass of individual molecules, to identify previously unknown VOCs in wine and wine grapes.

Eventually, winemakers may be able to use the data collected by scientists to tweak their growing and production techniques in favor of boosting or minimizing certain flavors, by controlling the conditions that affect VOC production in the grapes. But it will be “at least five to 10 years before this technology reaches commercial use,” Lund said.

Lund noted that plant biologists and biochemists should work with wine experts throughout the research process. “We want to make this of interest and use eventually to industry, and without the expertise of viticulturalists, it could go off on a tangent,” he said.

Art meets science

Lund is a wine drinker himself, although he admitted that he might drink too much coffee to have a professional-grade wine palate like some of his colleagues. His research on the molecular biology of wine has made him more, not less appreciative of what he drinks.

But are winemakers, notoriously protective of their profession as an art, open to the idea of a more scientific vineyard? Lund said winemakers, especially in the New World, have been very interested. “In this decade we are starting to see a lot of money flowing in” to VOC research, he said. The analytical approach may appeal more to large wineries than smaller makers because larger vineyards have more money to spend on the necessary technology, he suggested.

“Technology is weaving its way into wine making. We acknowledge that not everyone is going to want to use it but for those who do, it can be a powerful tool,” he said.