Chelsea Crump is only a little bit worried about having a needle poked into her eye next month. Thanks to her brother, and a lifetime of having a rare genetic disease, she’s pretty sure of what to expect.

Chelsea and her brother Tim have Usher syndrome, an inherited genetic condition that means they were both born deaf and are both now also slowly losing their eyesight. There’s no treatment for Usher now, but Chelsea and Tim are taking part in an experiment that they hope will at least stop their vision loss, and perhaps help other patients in the future.

“She took one look at Tim [after his surgery] and said, ‘That’s not so bad,’” said Linda Crump, their mother. Tim had the treatment in June; Chelsea’s is scheduled for October.

“It’s very minor compared to some of the other surgery I have had,” says Chelsea, 25, who lives with her parents and Tim in Portland, Ore.

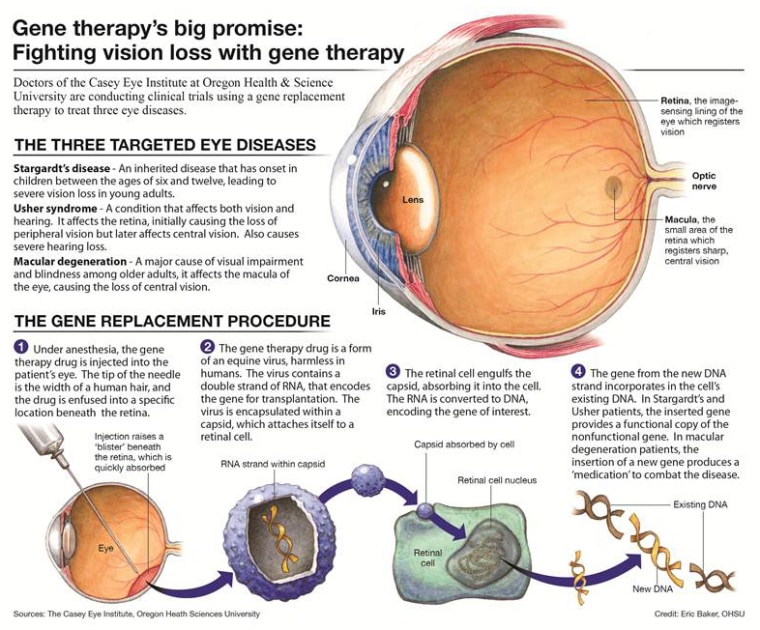

The needles deliver fresh, new DNA into the eyes of the four young adults volunteering for the trial. The technique, called gene therapy, is more than 10 years old yet it’s still a struggling field. But there have been a few successes lately that give renewed hope to researchers and patients alike.

Earlier this month, doctors reported they had successfully treated the first children in the U.S. for severe combined immune deficiency or SCID, sometimes known as “bubble boy” disease. Like Usher, SCID is caused by a mutated recessive gene, meaning children must inherit a defective copy from each parent. And like the Usher trial, the SCID trial included a brother and sister – Colton and Abbygail Ainslie.

In August 2011, doctors reported that two patients with a form of cancer called chronic lymphocytic leukemia had gone into remission after a type of gene therapy treatment that programmed immune system cells to hunt down and kill the leukemia cells.

The idea behind gene therapy sounds straightforward – if a disease is caused by a single faulty gene, then just swap it out for a healthy version. Especially for diseases that affect just one form of tissue, it shouldn’t be too hard. But it isn’t so easy to get the fresh DNA into cells and there is no guarantee that the patient’s cells will accept the new gene and use it.

Dr. Tim Stout, a surgeon at Oregon Health & Science University working on the study, says eye diseases offer a special opportunity, because it is easy to see if the treatment is working.

“You can see everything that is going on. I can look into the retina,” Stout told NBC News in a telephone interview.

It only takes minutes to inject the treatment – a virus genetically engineered to carry healthy DNA for the MY07A gene that is mutated in the form of Usher that Chelsea and Tim have. The researchers are using an experimental commercial product made by Oxford BioMedica. Called UshStat, it’s supposed to provide a lifetime of benefits with a single dose.

“We can put the drugs exactly where we want them to be,” says Stout. “That makes it very different from the lung or the liver or the pancreas.” And the eyeball is small and self-contained – the gene therapy product is unlikely to leak into the rest of the body, getting diluted or causing unwanted side-effects. The first patient to be treated, 29-year-old Michelle Kopf, had the surgery in April.

“From all that we can see so far, this is remarkably safe,” says Stout. The four volunteers cannot count on getting a benefit -- this is a phase 1 trial meant only to show the treatment is safe.

Usher, which affects as many as 50,000 people in the U.S., causes a slow degeneration of the eye’s retina that is called retinitis pigmentosa, or RP. It causes night-blindness and a loss of peripheral vision. Chelsea, as do many patients, first started noticing her vision loss when she was 10. It will slowly progress to blindness as she gets older.

“It is like tunnel vision. Their central vision is very good. They trip over things and they have night blindness and they can’t drive,” says Linda.

“I can see pretty well but I have the blind spots,” adds Chelsea, who has two college degrees and is studying to be a computer graphic artist.

“It’s depressing,” Tim, 22, chimes in. “And I can’t drive. You can’t see in the dark. I really can’t go out at night,” he adds. It can make his job at a senior living community difficult. “Sometimes I can’t see people and I bump into them. It’s embarrassing.”

Usher can cause balance problems too. The treatment won’t help those and it won’t affect their deafness. Both Tim and Chelsea have cochlear implants – devices surgically placed in their ears that give them fair hearing.

The results won’t be immediate. “It will take a year,” Tim says. “You can’t see right away,” adds Chelsea. Only one eye is treated. The other eye acts as a “control” to ensure that any vision changes aren’t happening because of something besides the treatment.

Linda Crump isn’t hoping for a miracle – just something to stop the ever-worsening loss of vision for her two youngest children. She has two older children who do not have Usher and she wasn’t sure about Chelsea or Tim at first. Like so many parents of children with rare diseases, she had no reason to suspect a rare genetic condition -- only 3 percent to 6 percent of U.S. children born deaf have Usher's and the test for the defective gene is not standard.

“They were born deaf. There were signs but nobody could really tell us it was Usher’s,” she said. Then she went to a seminar and learning about the balance problems that affect children clinched it for her. “I walked out of there knowing it was Usher’s,” she said. “All their milestones were late – all the things babies do, the sitting up. It made a lot of sense when we finally got them tested.”

The Casey Eye Institute team at OHSU is also testing gene therapy for two other inherited eye diseases -- Stargardt disease and Leber congenital amaurosis or LCA. Both of those trials should have some findings to report soon. A different LCA trial showed in 2008 that gene therapy did appear to restore vision in patients.

Casey chairman Dr. David Wilson said the center had to invest heavily, in part because it is so difficult to set up the testing to make sure a treatment is having an effect. “We realized early on that there were no reading centers that were designed for this purpose and had to build that infrastructure,” Wilson said. “This has to have people who can interpret the results of the tests and the data has to be stored securely and transmitted to the study sponsors.”

And they have to factor in the very real and strong desire on the part of the study volunteers to show that they are being helped. “These patients are really desperate for treatments,” Wilson said. “They are going through a fair amount. They do almost always report a positive benefit. That is why it so important to have an objective endpoint.”

The tests will be rigorous, Wilson says. “Almost any patient you treat knows they are going to be treated. They know which eye. These patients are really heroic because a lot of them know it will be only the later phase trials that are going to have a result, but they want to help others.”

The original version of this story incorrectly stated that Dr. Tim Stout operated on Tim Crump. He performed the procedure on Michelle Kopf.

Related links:

Treatment restores vision in rare eye disease