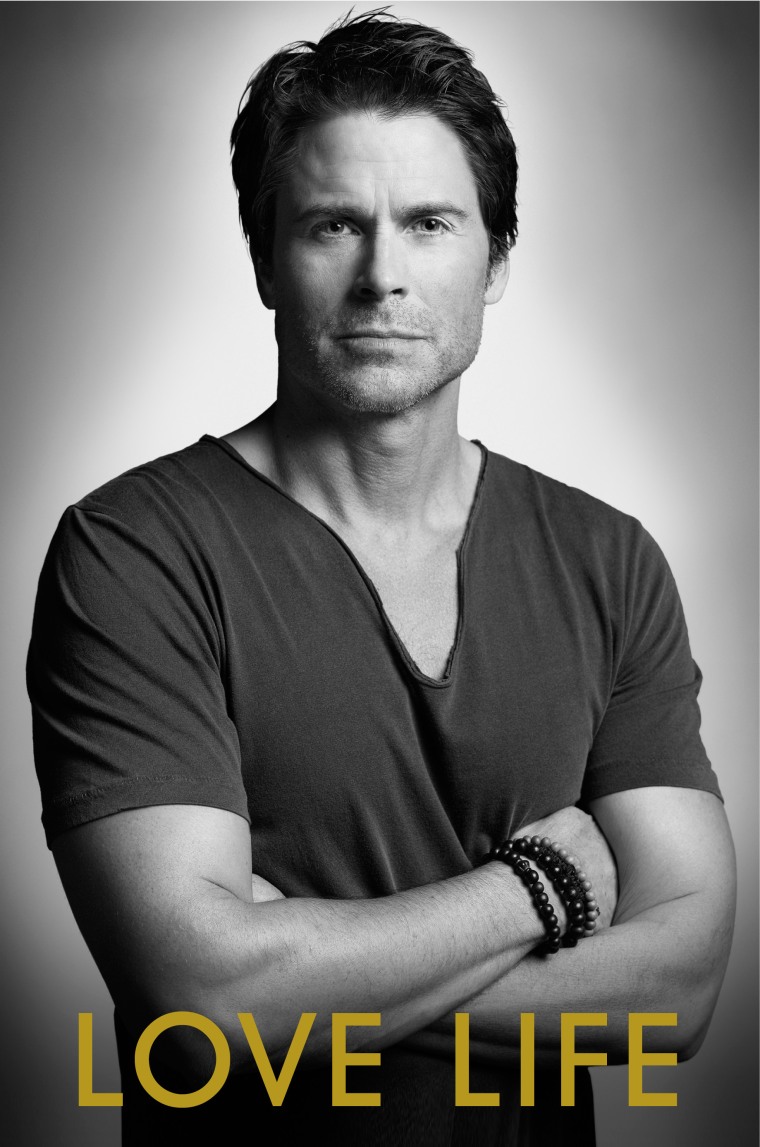

In Rob Lowe's new memoir "Love Life," the follow-up to his autobiography, "Stories I Only Tell My Friends," the actor delves deeper into his life and experience to ruminate on relationships, parenting and more. In this chapter, Lowe looks back with poignant candor at life with his growing son. Here's an excerpt.

Matthew applies to college

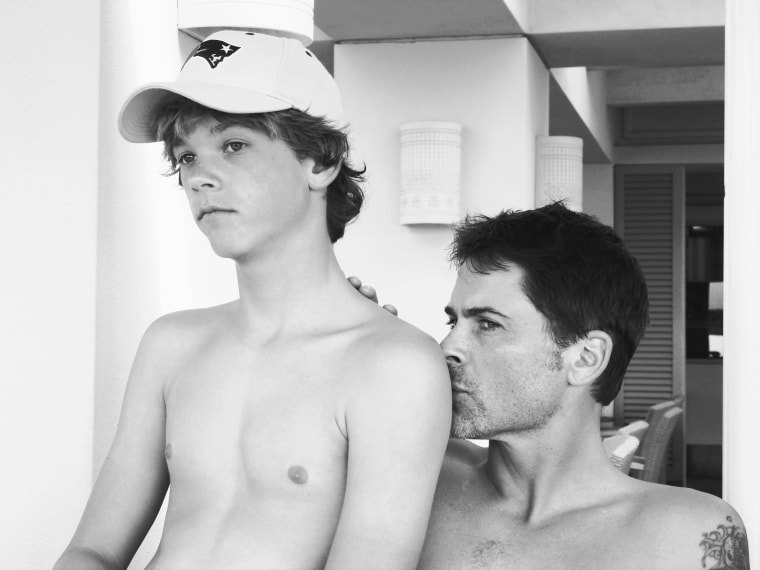

My son Matthew is eighteen. When I look at him, I often don’t recognize any part of the little boy I have loved for so long.

Sometimes I do; I’ll see a fleeting expression or the light will catch him in a manner that for a moment makes him look as he once was. With his size-thirteen feet and his mother’s long limbs, he can still look like a young colt navigating an open field. He has my love of history and politics, my interest in factoids, trivia and obscure information, most of it of limited interest to anyone else. Unlike me, Matthew is content to let you come to him, confident in his silences. He auditions for no one.

We’ve always been close, but I have come to realize our relationship has been predicated on proximity. We’ve loved reading together from the time he was a baby; we explored the hills and beaches and railroad tracks of our neighborhood. We ran in the yard with our dogs; we navigated the laughter, love and hurt of adolescence together.

Soon the geography of our relationship will change and we will build a new one based around distance, and while I hope it will be as close as before, I know it will never be the same.

Matthew is in the middle of the college application process. Choosing a school has always been an arduous and drama-filled travail for our family. I have only recently recovered from the great kindergarten search. After gaining a coveted meeting with a prestigious school’s admissions director, I watched my son jam a shark’s tooth into the woman’s ear. Why a supposedly learned child-care expert would have such a small health hazard within a child’s reach remains a mystery and should have been a sign that perhaps this fancy-pants school wasn't all it was cracked up to be. There were other signs that I chose to ignore as well.

While some of the school’s third and fourth graders carried books through the hallways, a larger portion carried skateboards. Having grown up in Malibu, I was not unaccustomed to Southern California’s less-than-respectful fashion ethos, but even I was taken aback by the sheer numbers of boys dressed like Jeff Spicoli. When we were touring a sixth-grade science class, a kid raised his hand with a question. “Pete,” the eleven-year-old student asked the teacher, who was in his midforties and wearing surf shorts, “what is more common, zooplankton or phytoplankton?” While I struggled to come up with the answer myself, I struggled even more with the concept of a little boy referring to his adult teacher by his first name. I was well versed in this sort of educational culture; in fact, my mother had placed my younger brother Micah in such a kindergarten in Malibu years ago, a local institution. The founder of the school didn't believe in “structured” teaching or apparently discipline of any kind. Whenever I picked my brother up from school, many kids were AWOL, running around in the hills above the school like savages. Even as a sixteen-year-old I had the notion that this was no way to run a railroad, so, years later, I was sort of relieved when Matthew took matters into his own hands and ended our application process with the shark’s tooth.

My wife, Sheryl, and I did eventually find the right school for him. I think we all react to the way we were raised as we try to navigate our roles as parents. Neither my mother nor my father was particularly involved in my life at school (although they did instill a work ethic and made sure all homework was done). With my own kids, I wanted to be as much a part of their school experience as I could, as did Sheryl.

For me, this meant taking part in as many school functions and extracurricular activities as I could. I coached both of my sons’ elementary school basketball teams. One of my fondest memories is winning the league championship for the school’s first time. (As Ty Cobb said, “it ain’t bragging if you’ve done it.”) Even though some of what I thought were my best motivation techniques were probably too advanced for sixth graders, I loved being with the kids. I’m not sure if they fully appreciated my grabbing them by the jerseys at half time, eyes blazing, and admonishing them with, “No one, and I mean no one, comes into our house and pushes us around!” When the kids looked at me with blank faces, I would tell them, “It’s from the film Rudy. You know, Ara Parseghian? The great Notre Dame coach? . . . Ah, never mind, just toughen up out there!” And you know what? Inevitably, they would.

I learned that kids are like actors on a set: They want to know that their director gives a s__t, has an actual plan and, just maybe, knows what he’s doing. In other words, they want leadership. And you can’t attempt to lead by being all things to all people or a slave to PC society—which brings me to why I was eventually overthrown as the basketball coach in a parent-led coup d’état and why they've never won a championship since.

Lots of kids wanted to play basketball in that sixth-grade class. I suggested that rather than having one huge team on which some kids would inevitably not get much playing time, we field two teams, with two different coaches, so the greatest number of kids could play. I then went through almost Manhattan Project–like analytics to ensure both teams were equally matched. But after my first few practices, I began to sense trouble.

A gaggle of moms had been eyeballing me throughout our first scrimmage game with the grade’s other team. It soon became clear that they were not fans of my methods.

“Why didn't my son play very much?” asked the ringleader with the same righteous fire as Norma Rae. I couldn't very well tell her that her boy had no interest in learning the fundamentals of basketball or playing basketball, and certainly not winning at basketball.

“We’re all just getting our footing out there. The more they learn, the more they’ll play. But your boy’s working hard,” I lied, and immediately hated myself.

Then the next mom spoke up. “I don’t see why you are dividing these boys’ friendships by letting your team win. These teams are from the same class!”

“You . . . You don’t want anyone to win?” I responded. I had heard about this new mind-set about sports in schools, but thought it was only a BS punch line for late-night talk show monologues.

“Well, I certainly don’t think you should be keeping score!” she answered. The other moms nodded gravely.

I explained that, in my view, the tradition of noting the amount of baskets achieved, adding them up and comparing the total to the other team’s is the only objective method to see who played better. The moms sniffed and looked at one another. I haven’t felt such tension and disapproval since I sang with Snow White at the Oscars.

“Well,” Norma Rae said with finality, “I don’t think it’s fair to have winners and losers.”

I thought about debating that point. In my estimation, there is no more virulent motivator in life than wanting to win.

As the season progressed, so did our team. We practiced hard, but always with an element of fun. Still, I could see that there was a type of parent who didn't want to have their kids do push-ups if they goofed off, or run laps if they were late, or get benched for a lack of motivation.

I loved these boys and loved coaching them. Telling a shy, awkward kid that he “can do this” when he clearly thinks he can’t, and has probably never been told he can, would almost move me to tears. When that kid made his only basket of the entire season, in our league championship, I wanted to run out and hug him. Instead, I gave him the game ball.

After winning the championship, I found out that there were no awards (or anything else) to memorialize the boys’ achievement, so I decided to buy each kid a small trophy myself. I had it inscribed with the school’s name, the year and the word “champions.” I soon heard from the school’s PE teacher that he’d been getting complaints from parents whose kids didn't win the tournament and so would not be getting a trophy. Furthermore, I was told that the kids would not be allowed to attend the awards/pizza dinner I’d arranged unless I got trophies for the other school team as well.

“Does anyone object to the winning team’s trophy showing that they were, in fact, the winning team?” I asked.

“Honestly; yes. But if all the kids got the same style and size trophy, I think you could get away with it.”

“Okay. Do you want me to pay for these additional trophies?” “Yes. That would be great.”

“What about the other coach?” I asked. I was happy to foot the bill but curious as to where the other team’s leader was in all of this nonsense.

“Oh, he says he’s done with the season.”

I held our awards dinner at our local pizza parlor, setting up an awards table on top of the Ms. Pac-Man machine. As I handed out the Golden Basketball Man to each kid, the television above us showed the Oscars being handed out down in LA. The pizza parlor was decidedly more fun and fulfilling. A few weeks later I was informed of a new school policy: Parents would no longer be permitted to participate in after-school athletic programs. This was probably as it should have been in the first place. The next year local college volunteers were brought in. I watched and rooted as an incredibly sweet and well-meaning young lady tried to figure out what a three-second violation was and how to inbound the ball correctly. Turns out she’d never played basketball; her expertise was water polo. The team went two for twelve that year.

Sometimes at pickup, waiting for my boys to get out of class, I would see my old team on the playground. We’d play a little horse. I’d teach them the Xs and Os, the fundamentals of the pick and roll, but they showed me something, too. From them I learned (or re-learned) how important adolescent friendships are, how impressionable young boys can be and how much male, adult attention means to their development. I learned that they rise to a challenge, crave it and desperately want a responsibility they can meet. I saw their humble appreciation of being recognized for a job well done. And I realized that maybe that’s all anyone really wants, including me.

———

When Matthew finally opens the college-acceptance letter that we all prayed would come, I know it will be the beginning of his life without us. This is almost too much for me to contemplate. I prefer to live in denial that my relationship with him will be irrevocably changed.

Instead I goad myself into focusing on the bright side of having my beloved firstborn leaving home, of having the empty bedroom full of his boyhood touchstones, the sudden quiet when his incessant techno dubstep electronic dance music no longer blasts through the floorboards down into my office as I try to read a script and maintain my sanity. Yes, instead I think about the amazing! fantastic! wonderful! gifts that will come from being completely cut off from his daily life and academic experience.

And those would be what, exactly? First and foremost: No more field trips to chaperone!

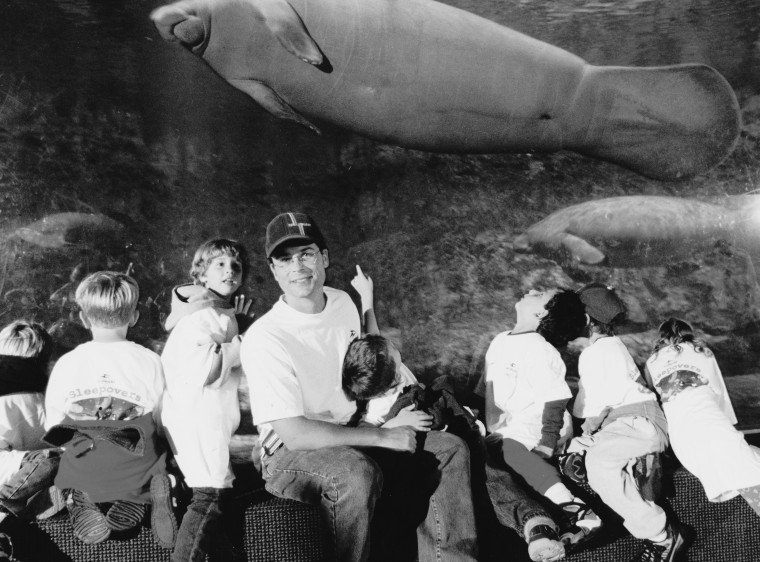

My wife, Sheryl, once volunteered me to chaperone my son’s third-grade class on a weekend trip to SeaWorld in San Diego, making Matthew and me captives in a six-hour van ride with a parent we barely knew.

In spite of being professionally gregarious, in my nonpaid hours I’m a bit of a hermit. After being around a crew of fifty people for twelve hours a day on a film set, I really like my alone time and as always I abhor small talk. I love to delve into subjects one doesn’t in polite conversation, but idle banter, after about ten minutes, makes me wish I was still guzzling kamikazes at the Hard Rock Café. Or, in severe cases, leads me to consider reenacting John Gielgud’s warm-bathtub wrist-slicing suicide scene in Caligula.

The van ride would provide lots of time to get acquainted with the other class dad. The boys sat in the back doing their thing. I was riding shotgun in what reminded me of Scooby-Doo’s Mystery Machine, but without the charming paint job.

Things went south quickly.

I had become suspicious of a Styrofoam cooler in the foot well between our seats and eventually the dad noticed.

“Help yourself to a cold one,” he said, opening the lid to reveal that it was packed with bottles of Budweiser.

Now, I’m not a lawyer, but I often play one on television, and I think I know enough about California law to be squeamish about having an open container of booze in the car.

I spent the rest of the drive on alert to his opening one for himself, but he never did. He must have been saving them for his tour of SeaWorld. Soon we were driving through the heart of Los Angeles, down the 405, the busiest freeway in the country.

“What do they call this city?” he asked, looking around in wonder. “Um, Westwood,” I replied, trying not to pass a judgment on him for asking that question when he’d just finished telling me he had lived in Southern California his whole life.

“So, this would be LA, then?” he asked.

“Yes. That is correct. We are passing through LA,” I answered. I thought, “Maybe I should have a beer.”

Later, at SeaWorld we met up with the other parents and kids and took our tour, which all the kids loved. Soon it was nighttime.

One of the dirty little secrets about having lived three-quarters of my life in show business is that I have developed a stress-reducing mechanism of only focusing on the matter directly at hand. This is great for navigating the uncontrollable uncertainty of life on film sets but probably not ideal for life in the real world. And so it slowly dawned on me that I hadn’t fully comprehended the reality of that night’s sleeping accommodations. I’m not a complete idiot; I knew I’d be participating in, and had packed for, a campout at SeaWorld. But I did not realize that we would be sleeping inside the manatee exhibit.

My traveling companion, now happily drinking his Bud, told me that this was a rare treat—SeaWorld offered this only to select schools. He then grabbed his son and bolted into the exhibit to “get a good spot to sleep.”

The manatee exhibit is an enormous tank/ecosystem with a crowded observation area and an underwater viewing area. The place is usually jam-packed with spectators, reminiscent of center court at Flushing Meadows. The elephant-like creatures float around lazily and sometimes stick their walrus faces out of the water for a slightly disturbing stare-down. But that night, as the park closed down, even the manatees were looking to get some shut-eye.

My son and I entered a bunker-like space under the grandstands. The air was thick and humid, oppressive to the lungs and cold. There were cement walls on three sides. On the fourth wall, we could clearly see the beautiful beasts swimming, in what seemed like slow motion. Apparently, ours was not the only school to be allowed this aquatic backstage pass; the place was infested with screaming, scrambling kids, several of whom, from the sound of their hacking, had debilitating head colds. Through their screeching, I could barely hear my son ask, “Where do we sleep, Dad?” I looked around. The parents and kids had staked out their areas, spreading out their sleeping bags. The floor was tough, hard industrial carpet over cement. I picked a spot in the corner away from the glass tank wall, figuring (correctly, as it turned out) that the light illuminating the tank was on for a reason and would stay that way through the night. I’m not a hothouse flower; I camp often and am not the type to bring air mattresses. I have also camped in the dead of winter. But this was different because I was surrounded by elements I could not control that would in all likelihood disturb my sleep. And know this about me: I. Like. My. Sleep. It probably is some sort of post-traumatic stress disorder left over from surviving the decade of the 1980s, where no self-respecting person ever slept. As I unrolled our matching Timberland sleeping bags, I hoped against hope that I could find a way to fall asleep among the hacking, yammering kids, floodlights from the tank illuminating the cold cement floor and gentle thumps of manatees banging against the glass.

I snuggled my boy up next to me (he was having a blast) and shut my eyes.

“Hi! Hi there! Rob, right?”

My eyes snapped open to see a mom dragging two kids behind her toward our little campsite.

“Hi! Hi! Hope you don’t mind, you seem to have such a great spot!” she said, unloading what looked like a week’s worth of supplies right next to me. “Box juice? Box juice?” she offered.

“No thanks, I’m just turning in for the night.”

“Cool. No problem. Someone said you were here and I didn’t believe them. I was like, what would Rob f___ing Lowe be doing at SeaWorld?!”

My son, who always appreciates the proper usage of a good piece of profanity, said, “My dad’s our chaperone!”

“Ooooh, he looks just like you!” she said, staring at him like he was a puppy in a pet shop window.

It was a rough night. I had a disturbing dream. In order to pay the bills, I was forced to star in a direct-to-DVD sequel to Free Willy, but with manatees instead. The plot centered around an emasculated dad (played by me) going through a divorce from his übersuccessful, highly strung wife (played by Sarah Jessica Parker, although at some point it was also the actress from Footloose—you know how dreams are). Our adopted Sudanese son took comfort and mentorship from a handsome whale specialist at the local aquarium (Scott Bakula, I think) and helped him save a sick sea elephant. After our marriage counselor (Paul Giamatti) fell into the tank during a “family healing day,” he was saved by the manatee and so was our marriage.

At some point, I awoke, startled, heart racing. I was relieved, just as I am when I awake from other recurring nightmares, of unwittingly drinking a fifth of alcohol or giving a speech while my teeth fall out.

I rolled over, trying to get comfortable on the cold, rigid floor, among the chorus of adult snoring and juvenile sniffling and coughing. The light from the manatee tank illuminated the room as if it were noon instead of three forty-five a.m.

My neighbor, the talky mom, was also wide-awake. And staring at me. I smiled uncomfortably. She kept staring, unblinking. I had a passing thought that she might, in fact, be no longer living.

“You don’t even remember me, do you?” she said in a flat, robot-like monotone that managed to convey an element of accusation and craziness. “We met. Before,” she said finally, without offering any additional information.

I meet a lot of people, doing what I do, and as a single guy in his teens and twenties who starred in movies and traveled the world, I made a number of acquaintances, many romantic, most wonderful, and a few quite dangerous and malignant. I chose my words carefully.

“I’m so sorry, forgive me, where did we meet?”

“The Sunspot,” she said, naming a horrific old-school nightclub on the Pacific Coast Highway that has been closed for over a decade. I had only been there once, in my wild phase, and my only recollection of the evening was a police car plowing at full speed into a row of parked cars and ensuing ambulances.

“Oh, yeah. Sure. Sure, right!” I offered with feigned dawning recognition, calculating that acknowledgment would be the safest and most polite response. (There are people and a number of actors who can pull off the blunt and unrepentantly honest “I’m sorry, I have no idea who you are,” but I am not one of them.)

This seemed to break her trance and soon the whole Fatal Attraction vibe had passed, and she returned to being just another parent surrounded by elementary school kids sleeping in a manatee exhibit.

“Well, good to see you again,” she said.

“You too.”

“Good night.”

The rest of the field trip was uneventful but fun; Matthew and I begged off returning in the Scooby-Doo van and took the train instead.

———

It is a wonder, what we remember. Small, seemingly forgettable details feel like present, hard-edged objects you could actually hold in your hands; major events go lost until jarred out of unconsciousness by a song or smell or getting reacquainted with an old friend. I remember that field trip. I can’t remember my sons’ voices as little boys. Time, unfolding in all of its mystery, moving both fast and slow, has made its edit. Some of the things that have fallen away, I try to remember as I hold on to my memories of Matthew as a child. Before they are replaced by those of him as an adult. Before he heads away.

There is a movie called My Dog Skip, starring my Outsiders costar Diane Lane. I do not recommend it. If you have a child, particularly one about to leave home, watching this film is to be emotionally waterboarded. The story follows a little boy through young adulthood through the eyes of his beloved Jack Russell terrier. It is a great, yet admittedly manipulative, meditation on family, youth and mortality, and I defy you to watch its ending sequence and not have to be medevaced out of your present location.

The boy, now a young man, prepares to go away to school and he worries about his childhood best friend, Skip, now so old and arthritic that he can no longer jump up onto his bed. The boy leaves home; the Jack Russell sits in the boy’s room waiting for his return. In the middle of the boy’s freshman year, Skip dies. The boy’s parents bury him wrapped in his master’s Little League jacket.

My son Matthew’s beloved dog is a Jack Russell. His name is Buster. Matthew picked him as a puppy, when he was tiny himself. They sleep together to this day under Matthew’s down comforter. The vet has told us that Buster has arthritis now and soon might need to be carried up our stairs. Matthew has asked me to do this for him while he is away at school.

“Will you take care of him for me, Dad?” he asks me one day, not long after we’ve returned from our college tour, greeted by Buster’s howling.

“Of course.”

I catch Sheryl’s eye but look away. We’ve both been preparing ourselves in our own ways for this new phase, and both of us are struggling.

“Thanks, Dad,” Matthew says, scooping Buster into his arms and heading up to his bedroom.

They take the stairs together, Matthew tucking his dog into the chest of one of my old shirts he’s now grown into. I watch him stride away, confident and happy. As I listen closely I can hear him talking to Buster.

“You are my good boy. And I’m going to miss you.”

Excerpted from "Love Life" copyright (c) 2014 by Rob Lowe. Used with permission by Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.